CRACKING DOWN ON RED CROSS VOLUNTEERS

HOW AMERICAN RED

CROSS OFFICIALS CRUSHED AN INSURRECTION

BY AGITATED, MISTREATED VOLUNTEERS IN NORTHEAST GEORGIA

By Barry D. Friedman, Ph.D.

Former Red Cross National Disaster Training Specialist

Presented at the Annual Meeting of the

Georgia Political Science Association

Savannah, Ga., February 21, 1997

Copyright

© 1997 by Barry D. Friedman

AMERICAN AMBIVALENCE ABOUT DEMOCRACY AND HIERARCHY

From birth, Americans are socialized by their parents and teachers to value the ethos of democracy. Whether the child studies Thomas Jefferson's stirring words in the Declaration of Independence that proclaim that "all men are created equal," or the child votes in an election for student council representative and is admonished by the teacher to respect the result of the democratic process, Americans develop a reverence for both the rights of the majority and the individual.

At the same time, because children must be trained to be obedient workers once they accept employment in a hierarchical organization, they are taught to accept the teacher's authority so that, eventually, they will acquiesce to the authority of a boss.

Because of the contradictory messages that alternatively value equality and inequality, Americans' commitment to equality, participation, and democratic aspects of social organization is incomplete and even unreliable when power-holders seek to subdue powerless members of society.

This article is a case study of the mistreatment of American Red Cross (ARC) volunteers who are (or were) affiliated with its Northeast Georgia Chapter, the headquarters of which is located in Gainesville. Chapter officials, in fact, "terminated" the volunteer status of three of these volunteers (including this author), in violation of ARC and International Red Cross regulations. The story of how the unity of the aggrieved volunteers was broken while the powerful chapter officials remained united and resolute provides yet another example of how the masses squander the influence that their numbers might provide by submitting to the will of society's less numerous power-holders.

ASSOCIATIONS IN AMERICAN POLITICAL THOUGHT

The American colonists had emigrated from Europe's feudal, class-based society, and founded a relatively classless society. With the classless society came a disadvantage not known in Europe: Because individuals were not bound naturally into an organized economic class, they could not count on peers to rush to their aid in an emergency. Out of necessity, American colonists learned to develop civic associations, by which they could count through prearrangement on their fellows to help them out in a jam. As the French sociologist Alexis de Tocqueville explained:

In aristocratic societies, men have no need to unite for action, since they are held firmly together. . . .

But among democratic peoples all the citizens are independent and weak. They can do hardly anything for themselves, and none of them is in a position to force his fellows to help him. They would all therefore find themselves helpless if they did not learn to help each other voluntarily.1

When Benjamin Franklin helped to found the nation's first volunteer fire department in 1736, he was recognizing that one individual's effort to put out a fire in his barn may be futile, but the efforts of a group of firefighters might save the day.

The relatively wealthy founders of the American republic harbored some fears about how associations might evolve into political factions, which might in turn overthrow the government because of greedy motivations. In advocating the ratification of the U. S. Constitution in 1787, James Madison spoke of factions fearfully in the tenth article of the Federalist Papers.2 But Madison believed that creation of a national system with a strong federal government would foster the development of countless factions that, in competing with each other forcefully for influence, would neutralize the threat that any one or two might have posed separately. With the completion of the ratification process, the literature of American political thought became more favorable toward private, voluntary associations. Tocqueville, in his brilliant 1830s work entitled Democracy in America, waxed eloquent and respectful about the American inclination to form an association at the drop of a hat. He wrote:

. . . [O]ne may think of political associations as great free schools to which all citizens come to be taught the general theory of association.3

Associations have been rhapsodized as "training grounds for democracy," because they gave Americans practice in democratic life. David Truman, in his 1951 work The Governmental Process, celebrated the influence of interest groups in American public policymaking. ". . . [M]ultiple memberships in potential groups based on widely held and accepted interests . . . serve as a balance wheel in a going political system like that of the United States.4

Other works suggest that the apparent democratic character of American society is a façade for the control that an upper echelon of wealthy, powerful individuals exercise. French political scientist Roberto Michels declared that there is an "Iron Law of Oligarchy," which establishes that in every system and organization a small, ruling elite rises to the top and dominates decision-making. As Grant McConnell then observed, if there is an "iron law of oligarchy," then how can associations be training grounds for democracy?5 The individuals who will form that elite are distinguished from the remaining members of the group by wealth, personality, skill, or other factors. In The Power Elite, sociologist C. Wright Mills traces policymaking authority to a power elite that dictates policy to a stratum of officials and administrators.6 These officials and administrators, in turn, compel the masses to comply with the prescribed policies. In The Liberal Tradition in America, Louis Hartz explains that the rules of American democracy afforded the American public the legitimate means to limit the power of the wealthy, but the public wasted the chance by ratifying the right of the wealthy to control society's economic resources. The wealthy conservatives of the United States realized that they were vulnerable to electoral defeat, and so they created a "church" of democratic capitalism.

As the [Benjamin] Harrison campaign approached, these [wealthy conservative politicians], not out of any particular social insight but out of the sheer agony of defeat, discovered the facts of American life. Giving up the false aristocratic frustrations of the past, and giving up as well its false proletarian fears, they embraced America's liberal unity with a vengeance, and developed a philosophy of democratic capitalism. Willy-nilly, the difference between America and Europe swam into the ken of their vision, and Daniel Webster, pounding away at what he had in common with everyone else, insisted that the "visible and broad distinction" between the masses and the classes of the "old countries of Europe" was not to be found in the United States. Calvin Colton, also pointing to Europe, said that "every American laborer can stand up proudly, and say, I AM THE AMERICAN CAPITALIST. . . ." Whiggery [i.e., the wealthy, conservative strand in the liberal movement] had finally hit on the secret of turning its greatest liability into its greatest advantage.

The "Law of Whig Compensation" is that the "American democrat" could have overcome the wealthy, but instead accepted the Whig program. Hartz continues:

. . . [T]he American Whigs were to be amply repaid for the humiliation they endured while their brethren were triumphant abroad.7

Thus, as in this case of the mistreatment of Red Cross volunteers, the aggrieved volunteers had an advantage in number, but they acquiesced to the power of those who had more fearsome titles in the Red Cross organization. Reviewing the literature that celebrates the multiplicity of interest groups ("pluralism") and comparing it to the current state of American democratic life, Thomas E. McCullough concludes that pluralism has failed to foster democracy and equality. ". . . [P]luralism supports the status quo and favors those in power," he finds. ". . . [P]luralism devalues democratic citizenship."8 Clearly, something has gone wrong in the effect that associations have on American democracy.

THE PUBLIC IMAGE OF VOLUNTEER ORGANIZATIONS

Volunteer organizations obtain the resources that they need to deliver services and to pay for their administrative services from a combination of sources. The sources include (1) wealthy donors and foundations established by the wealthy, (2) people of modest means, including workers who donate through the United Way and retirees who send checks directly to the charity, (3) corporations, and (4) governments. Charity fund-raisers who practice the art of "development" attract a steady flow of funds from wealthy donors through "planned giving" strategies that include donations of investments and provisions in wills. In return, the fund-raisers offer recognition to these donors and to corporations; the recognition might include a name on a building or membership in a prestigious recognition society. But to extract donations from people of modest means and from government sources, the volunteer organizations must develop an image of selflessness and nondiscrimination. The current Red Cross motto, "Help Can't Wait," suggests an organization totally oriented toward the effective, prompt delivery of aid to victims of disasters and emergencies.

The image is reinforced by pronouncements and circulars that promise fairness in the treatment of donors, volunteers, and service recipients alike. In its well-publicized VOLUNTEER 2000 study, the Board of Governors of the American Red Cross enunciated this set of principles:

1. We can broaden our nation's volunteer force by removing barriers to volunteering.

2. Volunteers are not "free."

3. Volunteers contribute more than meets the eye.

4. Volunteer does not mean "amateur."

5. Volunteers and the organizations they serve must meet each other's expectations.

6. Volunteers must never be exploited.

7. Volunteers make excellent middle and senior managers.

8. When recruiting volunteers, it is more important to place the right person in the job than to attract volunteers at random.

9. We can help shape government policies on voluntarism.

10. Everyone benefits when nonprofit organizations collaborate.9

The International Red Cross proclaims these seven principles that are recited repeatedly and reverently like a mantra by American Red Cross officials:

• Humanity. Born of a desire to bring impartial assistance to the wounded on the battlefield, the Red Cross is dedicated to preventing and alleviating human suffering wherever it may be found--both at home and abroad. Its purpose is to protect life and health and to ensure that human beings receive the respect they deserve. The Red Cross promotes mutual understanding, friendship, cooperation, and peace among all the world's people.

• Impartiality. The Red Cross does not discriminate concerning nationality, race, religious belief, class, or political opinions. It seeks to relieve suffering, giving priority to those in the most acute distress.

• Neutrality. In order to continue to enjoy the confidence of all, the Red Cross may not take sides in hostilities or engage at any time in controversies of a political, racial, religious, or ideological nature.

• Independence. All national societies that make up the Red Cross international movement are independent. While they are auxiliaries in the humanitarian services of their governments and subject to the laws of their respective countries, they must always maintain their autonomy; this enables them to act in accordance with Red Cross principles at all times.

• Voluntary service. The Red Cross is a voluntary relief organization not prompted in any manner by desire for gain.

• Unity. Only one Red Cross society is permitted in any one country. It must be open to all. The society must carry out its humanitarian work throughout its territory.

• Universality. The Red Cross is a worldwide institution. All societies have equal status and share equal responsibilities and duties in helping each other.

By the repetitious declarations of these formulas by the Red Cross and other charities, the public comes to believe that those who govern and manage such organizations are motivated by altruism. Members of the public, feeling senses of duty to imitate the altruism, or fearing pangs of shame if they fail to do so, "give 'til it hurts." However, the portrait painted by nonprofit public-relations offices is highly misleading. In the final analysis, those who govern and manage Red Cross chapters and most other nonprofits are nothing more than professionals who need to make a living. In character, temperament, and aspirations, they can hardly be distinguished from those who staff the profitable corporate sector.

WHAT VOLUNTEER MANAGERS AND BOARD MEMBERS

REALLY THINK OF VOLUNTEERS

It is a rather deep, dark secret that volunteer managers often harbor contempt for volunteers who respond to recruitment appeals. Paul J. Ilsley reports that some volunteer managers use "metaphors" to describe volunteers. "Expressions such as `the care and feeding of volunteers' suggest that volunteers are pets or zoo animals."10 While this author worked at a Red Cross chapter in Northern Virginia, the chapter's fund-raising director ridiculed the notion that "gerbils"--his particular metaphor for volunteers--should participate in chapter policymaking. Ilsley adds that the professionalization of volunteer organizations often causes the perceived role and importance of volunteers to deteriorate.

Rather than being simply welcomed as people who have a desire to serve, entering volunteers are screened, trained, supervised, and fitted into predetermined slots. They are treated like interchangeable objects rather than like people with individual interests and abilities. . . .

Managers who distrust volunteers are likely to stress strict lines of authority, carefully structured training programs, and rigid supervision even when organizational concerns do not mandate this approach. Volunteers serving under such managers rarely have an opportunity to participate in decision-making processes at any meaningful level. These managers see the success of their organization's programs as lying in their hands; to them, volunteers are simply one element of production.11

The Red Cross emphasizes that the organization is governed top-to-bottom by "volunteers." The members of the national Board of Governors are "volunteers." The members of the regional leadership committees are "volunteers." The members of chapter boards of directors are "volunteers." Sadly, these "volunteer" board members are often--or usually--elitists who, if truth be told, have a substantial distaste for the label of "volunteer," out of fear of being mistaken for the rank-and-file volunteers who directly deliver the organization's services. Linda L. Graff provided this startling revelation:

It is rarely the case in agencies where policies have been written to guide the volunteer component that policies apply equally to direct service and administrative (board, committee, advisory) volunteers. In the same way that so many board members refuse to consider themselves as volunteers (is it because they consider the label below them?), board members often think of themselves as outside (above?) the scope of policies written for volunteers. This type of two-tiered elitism among volunteer ranks has left administrative volunteering beyond both the control of, and the protection afforded by, risk management programs and policy development.12

Accordingly, when Diane J. Duca, a former executive director of the Girls Club of Denver, writes a manual on the care and feeding of nonprofit boards, she lays out a list of 21 ways to say "thank you" to board members. Here are some of them:

3. Ask a distinguished member to stand at the next board meeting and take a bow while everyone applauds.

7. Once a year, take out an ad in your local newspaper to list and publicly thank all your board members for their time and service.

9. Ask your clients . . . to write notes to board members expressing the value of the services they've received through or from your organization.

10. Give a little personal gift rather than, or in addition to, a plaque or certificate.

12. Scan your newspaper for mention of members or their companies. Cut out such articles and send it to the member.

17. Congratulate members on accomplishments and milestones achieved by their family.

18. Nominate your board members for community service volunteer awards.

19. Reward members with a trip to your local organization's national, regional, or state conferences or training programs.

20. Let the employees in a member's office know he or she is appreciated. Drop in with a batch of homemade bread of something of this nature for everyone in the office.13

Nothing in Duca's book discusses recognition of direct-service volunteers; one ought to wonder why these forms of recognition ought to be specific to board members and why direct-service volunteers who deserve the same forms of recognition should not be considered fully qualified to enjoy them, too. There are severe implications when the chapter executive director lavishes support and recognition on board members but not on volunteers in the field: The board members cannot possibly understand the frustrations of rank-and-file volunteers who are not being lavished with the same support and recognition, and therefore cannot possibly represent the volunteers' needs and interests. The fact that the board members are "volunteers" does little more than to satisfy the technical requirements of federal tax statutes applicable to nonprofit organizations.

As a result, it is often the case that the best deal that volunteers can get is to be "tolerated." James C. Fisher and Kathleen M. Cole write:

Although it is important to identify staff who mistrust volunteers, it is also important, and often more difficult, to identify staff who merely tolerate them. Their lack of enthusiasm for the participation of volunteers is communicated via subtle, negative messages, such as halfhearted greetings, lukewarm expressions of appreciation, "forgetting" to invite volunteers to staff meetings, and, in general, consistently giving minimal attention to the needs of volunteers. The impact of supervision of this nature becomes apparent in the increasing unreliability of formerly reliable volunteers and in the eventual departure of long-term volunteers from the organization.14

Nancy Macduff describes a similar scenario:

In some organizations there is a lack of communication that influences the very survival of the institution. Volunteers and staff are locked in adversarial roles detrimental to the health of the entire organization. This usually begins gradually and at first is noticed by few staff or volunteers.

Symptoms include the increasing use of "us and them" language.

Macduff attributes the poor relationship to the tendency of some volunteer managers to withhold information from volunteers for territorial reasons. "`Withhold information and you are in control' is the philosophy," she observes.15

Volunteers who feel mistreated come to resent the higher status that their oppressors are lording over them. The volunteers resent the fact that the volunteer managers are personally benefiting from the funds that the volunteers raise; on the other hand, the employees may perceive the volunteers "as being a direct threat to their livelihood." The continuing tension bodes ill for the productivity of the organization.16

VOLUNTEER MOTIVATIONS AND RIGHTS

Various research studies have been conducted to determine the personality of volunteers and the incentives that motivate them. Ilsley reports:

Many of the personality studies of volunteers that appear in the literature of voluntarism are contradictory. For example, one group of researchers . . . found that volunteers can be differentiated from people who do not volunteer by the former's possession of such traits as extroversion, achievement motivation, and conscientiousness. Another study . . ., however, focused on very different personality elements and portrayed volunteers as guileless and lacking in savvy, street sense, and self-sufficiency.17

But the effort to find "what volunteers are like" overlooks the fact that volunteers have a wide range of personalities and aspirations and that the incentives that motivate them vary. There are some volunteers who are drawn to repetitive tasks that do not require any need to make decisions. Some volunteers are drawn to militaristic models of work; such volunteers are entirely receptive to expectations that they obey commands from those who outrank them, while they expect those who are of inferior rank, in turn, to obey their commands. Again, quoting Ilsley:

To be sure, not every volunteer wants to be part of the organizational decision-making process, and having all volunteers take part in organizational decisions can greatly slow that process.18

But many, and perhaps most, volunteers want to be involved in decision-making at some level. Part of the reason why volunteers want this kind of input is related to one of the principal benefits of volunteering--the opportunity to learn new skills that can be listed on a résumé and that prepare the volunteer for more attractive employment opportunities in the labor market. The notion that volunteers have self-interests lost its element of surprise long ago, when it was discovered that volunteers want to obtain benefits from their volunteer work. Ilsley wrote:

[Because volunteers' motives are not solely or even mostly altruistic, v]olunteerism . . . can exist without altruism. Purely altruistic individuals, if they did exist, might present a problem for volunteer group managers because their motivation would not be susceptible to organizational control. Rather than pretending that volunteers do not seek rewards, the wise manager will concentrate on learning just what rewards they do seek.19

Accordingly, volunteer managers have developed lists of motivations that must be made available to recruit and retain volunteers. They include:

Opportunity to be involved in decision-making. Ilsley states that an effective way "for keeping volunteers motivated and helping their motivations evolve in positive directions" is to "[a]llow volunteers to participate in problem solving and significant decision making." 20

Learning experiences. Ilsley states:

. . . [V]olunteers often seek learning experiences in their work as a way of achieving goals related to personal growth. They also find learning enjoyable for its own sake.21

Recognition. Duca's aforementioned list of ways to express appreciation to board members is appropriately applied to rank-and-file volunteers as well. The latter do not have less of a need for appreciation than do the former.

Respect. Fisher and Cole warn that volunteers who are not respected by management will eventually recognize their unimportance; this will damage the volunteers' sense of loyalty to the organization.

Communication of the connection between the work of volunteers and the beliefs of the organization about itself and its mission is critical for fostering volunteer involvement. The relationship between volunteers and the organization is clearly evident in the attitude of organizational personnel toward volunteers and in the respect with which the organization treats volunteers. For example, volunteers who are not informed about a change in plans may correctly surmise that they are not important in the general scheme of things. However, volunteers who sense an organization's loyalty to them are likely to be motivated to return that loyalty.22

Contrarily, there are factors that are motivation-killers (or "turn-offs") and that drive volunteers away from the organization. The repellant factors include:

No opportunity for personal influence. Pearce suggests that "volunteers must perceive opportunities for personal influence in an organization prior to making a commitment to that organization."23

Meaningless rules. Ilsley warns: "Volunteers who feel that they are helpless to follow their own interests, constantly enmeshed in nets of seemingly meaningless rules, are not likely to remain with an organization for long."24

Workplace model. Pearce found "that the workplace model is inappropriate for volunteers. After interviewing volunteers and paid staff from several organizations, she discovered that volunteers possess less dependence on the organization than do paid staff and that volunteer motivation differs more according to the type of work than to the status level of a position."25

The inevitable conclusion to these findings is that volunteer managers have duties to volunteers who are interested in participating in the governance and decision-making of the organization. Managers have an obligation to involve volunteers in the making of decisions that affect them. Fisher and Cole state:

Paid staff who trust volunteers can be easily identified. They treat volunteers as equals, offer volunteers opportunities to take the initiative, and invite volunteers to attend regular staff meetings to offer opinions about organizational goals, programs, policies, and procedures.26

Managers must achieve a balance in their oversight of the work of volunteers--providing staff support when volunteers need it, and allowing volunteers to make decisions concerning their own work when the volunteers are self-sufficient. Fisher and Cole state:

When the organizational climate is good, paid staff are perceived as colleagues rather than adversaries; administrators are viewed as enabling rather than hindering; and volunteers believe that they are part of an important effort much greater than themselves. . . .

[Paid staff who trust volunteers] also allow volunteers a high degree of self-sufficiency in the work environment. . . .27

In exchange for their unpaid labor, volunteers are emphatically entitled to enjoy certain rights appropriate to their status and sacrifice. Ilsley comments:

. . . [M]anagers should never lose sight of the fact that the true strength of voluntarism lies in the forums it provides for involving citizens in public life and keeping our institutions alive and responsive. Making sure that volunteers participate as much as possible in all parts of an organization and that their input is welcomed and utilized is one of the most important parts of a volunteer manager's job, for doing so can produce both deeper volunteer commitment and a more viable, flexible organization. The following suggestions may help volunteer coordinators increase volunteer participation and input.

• Allow volunteers to have a voice in designing procedures. . . .

• Allow volunteers to take part in organizational decision making. . . .

• Encourage volunteers to examine, express, and act on their values. . . .

• Provide forums in which volunteers can discuss ideas, opinions, and feelings. . . .28

The reward for the organization that provides this recognition of volunteer rights and that shows a respect for volunteers is loyalty from the volunteers. Speaking of public-sector volunteer programs, Jeffrey L. Brudney observes:

Just as for paid staff, citizens [volunteers] are more likely to accept and endorse organizational policies and programs, and to generate useful input regarding them, if they enjoy ready access to the decision-making process. Participation is key to empowerment of volunteers. . . . Empowerment is thought to result in increased feelings of personal commitment and loyalty to the volunteer program by participants and hence greater retention and effectiveness. . . .29

DEPRIVING RED CROSS VOLUNTEERS IN WHITE COUNTY, GA., OF

INFORMATION AND STAFF SUPPORT

The American Red Cross (ARC) is a quasi-governmental agency chartered by the U. S. Congress to deliver services to disaster victims and to military families. The "national sector" of the Red Cross delivers some of its services directly, such as the response to a disaster of sufficiently large scope to defy the ability of a local Red Cross chapter to cope financially with the magnitude of the disaster. When there are smaller disasters, such as damage to a few homes in a neighborhood, the local chapter is obligated to provide disaster services on its own accord.

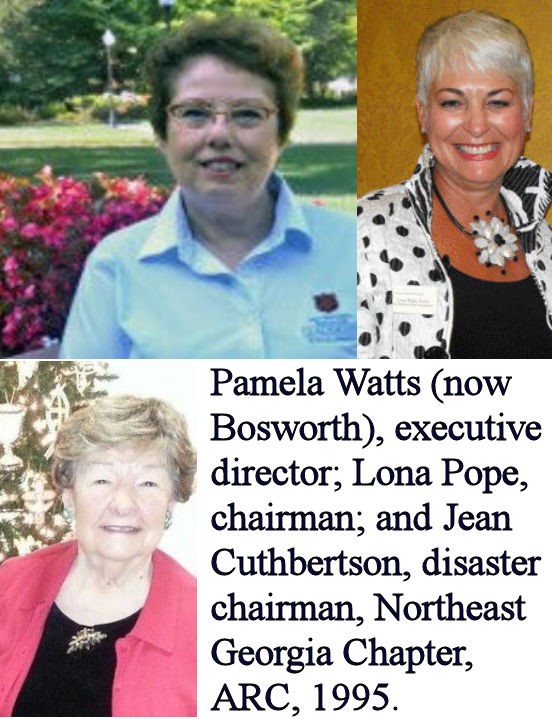

The Northeast Georgia Chapter is headquartered in Gainesville and serves eight counties. Some of the counties are moderately mountainous; other counties lie at the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains. It is governed by an unpaid Board of Directors. In 1995, its structure for delivering services to disaster victims was headed by a Disaster Services Committee, chaired by board member D. Jean Cuthbertson, a volunteer with more than 50 years of service to the ARC. As education officer for disaster services, this author was a member of Cuthbertson's Disaster Services Committee, and was responsible for providing training courses for new disaster volunteers and for scheduling instructors to teach these courses. In each county, there was supposed to be a Disaster Action Team (DAT) consisting of volunteers trained to provide forms of relief to victims of single-family fires and other small-scale disasters. This author was captain of the DAT in Lumpkin County.

Red Cross chapters offer frequent disaster training courses; many of them are poorly attended. But in March 1994, tornadoes ripped through Northeast Georgia. Many counties were affected; one of the counties that sustained the most damage was White County, a hilly area that includes the tourist-attraction city of Helen that attracts thousands of visitors by using a German Alps theme. White County's Red Cross DAT captain, Bill Usher, rose to the occasion, working feverishly to deliver resources to those driven from their homes so that they could return to their homes or be placed in alternative housing arrangements. Other than the Miller family--Bob Sr., Norma, Bob Jr., and Frankie--there were virtually no other Red Cross disaster volunteers in the community. The occurrence of disasters sometimes rouse the apathetic from their inactivity. From this state of heightened awareness emerged Barbara B. Hipp, whose energy for volunteer service was astounding. She offered to recruit Red Cross disaster volunteers so that White County would not have to rely on a small corps of overworked disaster-relief volunteers if a similar event were to occur.

Hipp began to identify scores of volunteers. When the first disaster-training course following the disaster was offered, the instructors arrived in Cleveland, the county seat, to find 60 eager trainees! On Hipp's initiative, scores of volunteers continued to demand training and to await activation as Red Cross disaster volunteers. As education officer, this author frequently visited Cleveland, Ga., to instruct training courses and scheduled fellow instructors to do the same. The number of courses offered at the chapter headquarters in Gainesville diminished as Cleveland became the focal point of activity in the Northeast Georgia Chapter.

In January 1995, as she had done in previous months and would do in subsequent months, Hipp called this author to request that more training classes be offered. Having agreed on arrangements to that effect, she changed the subject and lamented that no meetings of the county's DAT were being held and that the DAT captain, Usher, appeared to be reluctant to return her calls. This author counseled her to ask Usher to call a meeting by a date certain; in his failure to act by the deadline, the author suggested, Hipp should call a meeting of her recruits on her own initiative. Usher explained his own reluctance later, telling the author that his volunteer work after the March 1994 tornadoes had exhausted him, and it was a very long time before he felt the urge to resume his leadership activity. Nevertheless, Hipp was inexperienced as a Red Cross volunteer and could not justify circumventing Usher by calling a meeting herself.

Thus, the standoff continued, with Hipp recruiting volunteers and arranging for them to be trained, and with Usher declining to call a meeting. It is apparent that Pamela P. Watts, the chapter's executive director who had come to the Red Cross chapter from the Salvation Army, decided to side with Usher, a member of her Board of Directors. Hipp and her volunteers continued to be frustrated and baffled by the lack of staff support.

This author called his committee chairman, Cuthbertson, in May to alert her to the continuing frustrations of the White County volunteers. Cuthbertson responded that the White County volunteers were failing to use proper channels. Her response agitated this author, who finally demanded to know the circumstances under which "this chapter is a democratic organization." Cuthbertson responded that the chapter is a democratic organization "when the Board of Directors is elected at the annual meeting." The response provoked this author into a tirade about the supposed democratic nature of volunteer service and the absurdity of being a volunteer in such an undemocratic structure. Apparently, Cuthbertson reported this author's tirade to Watts, who invited me to a meeting in her office.

As the meeting began, I expressed my concern about the frustration of Hipp and her White County volunteers. Watts replied that I was otherwise an excellent education officer, but that I had allowed myself to be diverted by matters that were not my concern. She added that interference by experienced outsiders in the affairs of the new volunteers in White County had a divisive potential that could destroy the cohesiveness of this group. She demanded that I refrain from interfering in the working of the group. She also assured me that (1) the county advisory committee, of which Hipp was a member, was in control of the operations of the White County DAT and (2) Watts herself was taking her own advice and staying out of the internal dynamics of the White County DAT. After the meeting, this author wrote to Watts on May 15:

I believe that the chapter's progress is impeded by the chronic shortage of volunteer labor. I am not sure why this condition exists. From my admittedly poor observation point in Lumpkin and Dawson Counties, I have some guesses about underlying causes of our problems.

First, I am in doubt about the efficacy of the chapter's volunteer personnel function. Manifestations of volunteer recruitment, retention, and recognition are hard to come by. Just as an example, for the past couple of years, I have struggled to arrange for a 50-year volunteer pin to be awarded to Jean Cuthbertson, who this year observes 54 years of volunteer service to the Red Cross. The goal of causing Jean to receive this pin has been most elusive.

Second, the case of Tom Crowell is instructive in learning about how the chapter can discourage a superb volunteer. It appeared a couple of years ago that Tom was in line to become chairman of the Disaster Services Committee. The word came down, apparently from the Board of Directors, that Tom was deemed ineligible because his residence was outside of the chapter's service area, although he worked for a Gainesville employer that offered tangible support to the Red Cross. I wrote to Ronda Benson, chairman of the board's Nominating Committee, to express my opposition to a policy that threatens the linkage between Gainesville employers (who collect funds for the Red Cross through the United Way) and the chapter. I never received any response. Subsequently, Tom--who instead of being disaster chairman was holding the [inferior] position of captain of all DAT captains--noticed that he was not being contacted when disasters occurred in the chapter's service area. He became increasingly active in the Metropolitan Atlanta Chapter as his connection to our chapter dissolved. This anecdote is of interest because it is virtually impossible to offset the loss of a Tom Crowell. Talented disaster volunteers are very difficult to find. If we lose a Tom Crowell, the difficult effort of finding someone like him--if there is anybody like him--doesn't increase our volunteer strength. It just brings us back to where we started.

I wonder whether the chapter Board of Directors has much of a connection to the rank-and-file volunteer staff. In the course of my volunteer work, I don't see board members very often. The refusal to absorb Tom into the board may be indicative of a conscious effort to keep the board and the rank-and-file volunteer staff separated.

Third, communication between the chapter and volunteers has been slow and inadequate. It took quite a while to sell the concept that volunteers ought to receive a calendar of training opportunities on a regular basis. I personally have experienced difficulty in getting answers to questions. The matter of Jean's recognition is an example; I was told long ago that she would receive a pin at a board meeting, and was surprised within the last few weeks to discover that she has yet to receive it. My complaints about missing items that are packed for the disaster courses that I instruct result in assurances that the problem has been resolved, but the problems recur. We need to be able to trust in assurances that certain actions will be taken.

In June 1995, Lois and Richard Payton, a retired couple, were appointed to the paid position of coordinators of emergency services. They agreed to accept one salary for the full-time work that both of them would do. Since April 1994, they had been doing paid work organizing two counties that neither were in the chapter's service area nor had their own chapters; the coordinator position was a promotion. Before that, Lois Payton had been a Red Cross volunteer for 28 years; her husband had been a volunteer for four years. Because of their volunteer experience, they were able to identify with the White County recruits who were clamoring for information and staff support. The flow of information finally began between the chapter and the White County volunteers.

In August 1995, Hipp called this author again to schedule classes, and again proceeded to lament her experience with the chapter's management. This time, she told this author that she had planned to serve barbecued hamburgers and hot dogs at a DAT meeting, and that Watts had called from Gainesville to denounce Hipp's plan as an interference with a chapter-wide volunteer-recognition picnic scheduled for a month later! Hipp also notified the author that, at a meeting of the county advisory committee, Hipp and her fellow members were told of Usher's resignation as DAT captain and--contrary to Watts' claim that the White County group was self-governing--that a new captain had been installed upon the authority of chapter headquarters. The news angered this author, who had been assured in his June meeting with Watts that she was allowing the White County group to govern itself.

The inexplicable resistance against Hipp's well-intentioned and self-sacrificial efforts motivated this author on August 22 to announce his resignation as a member of the chapter's Disaster Services Committee, as education officer, and as captain of the Lumpkin County DAT effective September 30. (I declared that I would continue to be an instructor of disaster-volunteer training courses and first-aid and CPR classes.) Two days after the resignation was effective, this author called William G. O'Leksy, a member of the chapter board and of the Red Cross State Service Council, and asked that he and other board members review Watts' role in the obstruction of the activation of the volunteers in White County.

By coincidence, a day later, Watts moved to curtail the Paytons' work in providing staff support to the White County volunteers. In an October 3 memorandum, she gave them this astonishing instruction:

. . . Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday[ ] will be field days with your field time (between now and December) broken out as follows: Habersham [County] 75%, Hall [County] 10%, Stephens [County] 10% and Rabun [County] 5%. Since this position is not limited to a 40 hour work week, there may be some additional time required. This time would be in support to the Disaster Leaders of other counties (but not to their volunteers or their activities).30

Although the deprivation of staff support to the White County volunteers had been in effect for about a year, this memorandum is the only documentation that records Watts' policy of leaving the volunteers bereft of information or staff support which they needed and to which they were entitled.

Lois and Richard Payton flatly declined to participate in the neglect of the White County volunteers and the needs of the other seven counties as they perceived that Watts was instructing them to do. One day later--October 4--they resigned their joint position effective October 31. In their memorandum to Watts, they wrote:

We understand the direction in which you and Jean Cuthbertson are plotting for the Emergency Services Department[;] however, we feel we are not the ones to take you there. This therefore is our letter of resignation.

. . . We will continue to volunteer in disaster services and perhaps it would even be possible for Lois to return to the Board of Directors, [resuming her volunteer] role in public affairs.

This author began to receive calls from frustrated co-workers of the Paytons at chapter headquarters and from White County. Hipp called me to state that the White County volunteers were up in arms over the circumstances that caused their only sources of staff support to disappear from the chapter headquarters. At a White County DAT meeting of October 10, chaired by the new DAT captain, 20 White County volunteers adopted this resolution.

The executive director of this chapter has become notorious among the volunteer and professional staff for her practice of heavy-handed, vindictive management. Her concerted efforts to dominate every aspect of decision-making in the chapter have relegated its other constituents to the role of errand boys and girls. These efforts have deprived both volunteers and professional staff members of the opportunity to implement their ideas for enhancing the quality of Red Cross services and to enjoy their Red Cross experience. . . .

Volunteers are entitled to receive certain considerations in exchange for their unpaid work. These considerations include the right to enjoy their volunteer work, to innovate and learn, to participate in decision-making, and to be treated with respect. Volunteers are not to be treated as cheap, unskilled labor. Indeed, if we know that as Red Cross volunteers we are doomed to be shut out of decision-making and to be subjected to hostility, then it is irrational for us or anybody else to donate our labor to the chapter.

We are left with the decision of whether to resign or to struggle to restore this chapter to its appropriate direction. Over the years, some individuals reluctantly have chosen the former option. At this time, we choose the latter option. The Northeast Georgia Chapter is a resource for the people of this area, and they--and we--have a right to expect that it will serve all of its stakeholders fairly and efficiently. We, therefore, expect that clients, volunteers, employees, and the rest of the public will have a Red Cross chapter that operates in a humanitarian and enlightened fashion. To this end, we demand a change in the operation of the Office of the Executive Director. Preferably, this will involve an unconditional commitment from the executive director to accept members of the volunteer and professional staff in a partnership in which all can participate and all can benefit from their roles in this organization. In the absence of this commitment and of action consistent with this commitment, we request that the executive director be replaced. Should the chapter Board of Directors ratify the hard line of the executive director, we will reluctantly but determinedly seek other appropriate means to change whatever personnel have orchestrated the mistreatment of loyal Red Crossers.31

Hours before the meeting, Watts and Chapter Chairman Lona P. Pope met with the Paytons, blamed them for igniting the anger that was kindled in White County, demanded that they quell the rebellion, and threatened to "blackball" the Paytons from further service in the Red Cross organization. Watts and the Paytons appeared at the meeting, where many of the volunteers excoriated Watts and demanded that the Paytons' resignation be rejected. The next day, Watts began the process of expediting the Paytons' separation from the paid staff.

The executive committee of the Board of Directors received the protest statement, and huddled to decide what to do in response. It issued a letter to the White County volunteers, professing to be perplexed by the protest and requesting more information including responses to a questionnaire that it designed. Many of the angry volunteers responded, providing the executive committee with more than 80 pages of written testimony.

[Image inserted after 1997] |

CRACKDOWN ON RED CROSS VOLUNTEERS

The executive committee of the Board of Directors finally responded at a meeting in Cleveland, Ga., on November 9. Chapter Chairman Lona P. Pope opened the meeting by announcing that she would read a statement and then terminate the meeting, because chapter leaders had heard enough. The statement said:

The Board of Directors has reviewed both the protest letter and all materials sent in. We requested proof of the allegations but found very little. We have spent hours pouring over the printed matter and have determined many of the statements were either misunderstandings of procedures and proper channels by which work is accomplished or ignorance of these.

In order to correct this situation from happening again, an official Red Cross Orientation will be required of volunteers. This orientation will include a manual of volunteer policies/procedures, job descriptions for all volunteers, a code of conduct and written contract to be signed. . . .

The chapter has made excellent progress under the leadership of Pamela Watts, our Executive Director. We have doubled our membership, increased our presence in the counties, become financially solvent, begun new programs and constantly look for and plan for better ways to serve our constituents. She has strong support from the board in her management of the chapter, her decisions and the direction she has taken for our chapter. The Board of Directors is a hard working, representative, volunteer group of concerned, caring people. Many hours are spent reviewing, studying, fine tuning and planning in all areas of the chapter's work. . . .

The Board and staff are honor bound and committed to make the Northeast Georgia Chapter a vital, living, breathing entity in these mountains. We challenge you to do the same. . . .

Accompanying Pope and Watts to the meeting was Michael L. Bennett, executive officer of the Southeastern Region of the Red Cross. Bennett arose and pronounced the policies and decisions of Watts and the executive committee to be in good order, consistent with ARC policies. Perhaps, then, it was also in good order when, the next day, Pope called Lois and Richard Payton and told them: "After reviewing the White County report, the Northeast Georgia Chapter decided we can no longer use you as employees or Volunteers."32 The quotation might not be exact; as Pope read from written notes, the Paytons repeatedly asked her to "slow down" and finally asked for a written copy of the termination notice. The document never arrived. The Paytons requested a meeting with the chairman of the board's Human Resources Committee, Johnson T. Black, who ruled that the Paytons had not been treated maliciously. Their termination was upheld. The "blackballing" threat against the Paytons was taking on new meaning as Lois Payton's 28 years of volunteer service to the Red Cross had earned her not the least bit of mercy.

The executive committee of the chapter board also called for discussions involving personnel chairman Black and the members of the chapter's paid staff. However, some of the employees reported that Watts attempted to intimidate them into silence, telling them at a staff meeting:

I have something on each one of you. [I have heard s]pecific things that have to have come from staff members. If you discuss this with each other [or with] volunteers or board members, I will know because everything gets back to me. If I find out you will have the problem. You need to decide right now if you want to provide services for the ARC or you may want to seek employment elsewhere.

Anything you say may be recorded. It could wind up in print. You may be called before a committee or you may be called before a court.33

Thus, the personnel chairman held the meetings with employees, but the employees were terrified to divulge any information that might help to restore the chapter's credibility but that would cost them their careers.

Some of the complaining volunteers, including this author, understood the November 9 letter from the executive committee to amount to a crackdown on the volunteers. A Red Cross code of conduct had been in force throughout the events described in this article, but the written contract seemed certain to be the instrument by which the executive director could henceforth terminate volunteers, possibly without any due process. This author, with the concurrence of several of the volunteers, wrote an appeal of the executive committee's response to the entire Board of Directors for presentation at the board's meeting of November 16. The appeal stated:

The written decision of the Executive Committee is an abomination. "We requested proof of the allegations," the committee wrote, "but found very little." How 83 pages of written testimony from earnest but beleaguered volunteers can be "very little" proof is a mystery to us. The committee reinterprets the testimony as "misunderstandings of procedures and proper channels by which work is accomplished or ignorance of these."

The written decision goes on to prescribe procedures that will foreclose a recurrence of the problems. The procedures amount to a vicious crackdown on every volunteer in the chapter below the level of the board. If implemented, these procedures will not strengthen the Board of Directors. Instead, they will isolate the members of the board by virtue of driving committed volunteers away from the chapter more effectively than anything that the executive director has been able to accomplish. Accordingly, we emphatically and urgently call upon the board to overturn the vindictive, repressive decision of the Executive Committee and to turn to other, more rational individuals to design a resolution of the problems that were described in the statement of protest.

The thrust of the Executive Committee's plan is to require that every volunteer attend a revised orientation, at which the board would impose a strict chain of command. Orders given by the Board of Directors and interpreted by the executive director would control every action taken by any volunteer. The extent of control appears to govern all of the following:

• The form of a volunteer's expression of dissatisfaction with directives that he or she is given.

• The determination of the leaders who will lead the volunteers at any level.

• A volunteer's desire to help Red Cross volunteers who live on the other side of a county boundary, or volunteers' desire to invite Red Cross volunteers from other counties to assist them. Although the chapter is a multi-county entity, the Executive Committee would transform county lines into "Iron Curtains" that cannot be crossed except at risk of termination.

• The kind of refreshments that are served at volunteer meetings. . . .

The [board's] control will be accomplished by the requirement that every volunteer attending the revised orientation must sign a "written contract." The "written contract" undoubtedly is an instrument recording the volunteer's agreement to acquiesce to control by the board without any compensating benefits. The only value of the "written contract," from the Executive Committee's point of view, is that it will provide the Executive Committee with a basis for terminating an individual's volunteer status if he or she runs afoul of the directives of the regime.

. . . [T]he entire [response from the executive committee] describes a system designed solely to extract obedience from every volunteer below the level of the board. This approach is alien to a democratic society like the United States, and constitutes a provocation for every individual who is committed to the notion of democracy and equality. . . .

Roberto Michels wrote of an "Iron Law of Oligarchy." In every system, he said, a few individuals rise to the top like cream, because of certain characteristics that they possess--charisma, intelligence, leadership ability, possession of wealth, or other attributes. However, even oligarchs must provide incentives for other individuals to remain in the system. The Executive Committee proclaims the board to be "hard working, representative, . . . concerned, [and] caring." In what way is the board representative? Of whom? The board can be representative if it reflects the will of the volunteer staff. If the board accepts the repressive report of the Executive Committee, it will have no constituency of any kind, except for itself. Its legitimacy to govern this chapter will have dissolved, and it will henceforth be embattled.

The Executive Committee is prepared to set about the task of driving volunteers out of this system, following on the example set for several years now by the executive director. When the Executive Committee boasts that the chapter has "doubled our membership [and] increased our presence in the counties," it fails to explain why so many counties have lacked even one individual capable of writing disbursing orders for disaster victims, and why volunteers in the only county that has developed a truly successful Disaster Action Team--i.e., White County--have been targeted for reprisals and ostracism. Clearly, the executive director and the Executive Committee, given the preference, will choose a pathetically small volunteer workforce instead of a larger, active, and involved workforce that threatens their unstable grasp on control. . . .

The Board of Directors has a responsibility to the people of the chapter's service area to provide an inclusive, equitable, and humanitarian Red Cross chapter. Acceptance of the Executive Committee's intemperate, vindictive decision would discredit the board and the chapter. The board must overturn the ill-conceived plan to impose a totalitarian system on the volunteers of this chapter. We are available to work with the board to bring about an amicable resolution to these complaints. The alternative--the implementation of a crackdown--assures the board of nothing but a protracted struggle to rescue the Northeast Georgia Chapter from those who underestimate the ability and the right of volunteers to participate in the governance of their organization.

This author appeared at the board meeting at chapter headquarters with this statement, expecting a large number of the White County volunteers to join him in the continuing protest. But the tide was beginning to turn. Toni Busch was the only volunteer from White County who had the courage to confront the entire board. Chairman Pope adjourned the meeting without recognizing this author or Busch; I arose as the board members were having their refreshments and receiving door prizes and yelled that Busch and I had delivered the appeal letter and distributed a copy to each of them. We were ignored.

Six days later, the crackdown was escalated. This author received a certified letter from Pope and Watts saying:

Everyone has a right to their feelings about issues and may not always agree with all policies and procedures of the organization they have pledged to support. When that support is disruptive and contrary to the best interest of that organization the individual needs to leave that organization and locate one of more common interest.

The Northeast Georgia Chapter, American Red Cross, has tried to answer your inquiries and accusations in every way but to no avail. Therefore, we feel your services will no longer be needed and hereby terminate our relationship.

Thus, this author became the third volunteer to be terminated from Red Cross service, without due process. Combined, the three outcasts had accumulated 41 years of unpaid volunteer service to the American Red Cross.

ARC OFFICIALS THWART THE VOLUNTEERS' ATTEMPT TO APPEAL

This author thus made plans to appeal the volunteer terminations. He urged Hipp and the other complainants to join with him in the formation of a "Committee for a Principled Red Cross." He wrote to Carol H. Rittenhouse, manager of ARC's Georgia Field Services, and to Bennett, executive officer of ARC's Southeastern Region, asking for the names of statewide and regional volunteer policymakers, so that the complainants could alert these officials to the acrimonious situation in Northeast Georgia and request intervention. Just as the executive committee of the Northeast Georgia Chapter's board had declared the board to be "representative" of the volunteers, so the statewide and regional volunteer policymakers were "representatives" of the volunteers, too. Incredibly, Rittenhouse and Bennett declined to divulge who Red Cross volunteer leaders might be! They instructed this author to communicate only with the chairmen of the State Service Council and the regional committee. On January 9, 1996, this author wrote to ARC officials at the local, state, and national level, and invoked the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), on account of ARC's quasi-governmental status, to obtain the names of Red Cross leadership volunteers at the state and regional levels. Rittenhouse, who had originally agreed to release the state list and then reneged, reversed herself and finally released the state list. But Bennett continued to conceal the names of the members of the regional committee. On January 25, 1996, this author received a letter from Katherine Simonetti, associate general counsel in ARC's Office of the General Counsel in Washington, D. C., with this reply to the FOIA request:

In response to your letter of January 9, 1996, which you copied to Richard Dashefsky, General Counsel, please note that as the Red Cross is not a government agency and makes no governmental decisions, it is not subject to the [FOIA]. Consequently, the Red Cross is not obligated under FOIA to provide to you the information which you requested.

Understand, then, that the Red Cross wants your money, unpaid labor, blood, and bone marrow--but for its part it prefers to operate in secrecy and to be governed by committees shrouded in anonymity.

The Paytons' appeal of the termination of their volunteer status met with the same wall of obstruction and silence. Their December 8, 1995, appeal to Mari Anne Eby of ARC's Office of General Counsel; Bennett; Rittenhouse; and Georgia Cluster 1 volunteer disaster leader Don Shedd was acknowledged only by Shedd. The state, regional, and national offices of ARC ignored their inquiry; this is what 32 years of combined service as Red Cross volunteers will buy.

The White County volunteers observed the response that lay in store for dissidents in the Red Cross organization. The last holdouts had one final meeting with Ann Rice and Cherry White, members of the Northeast Georgia Chapter's board who carried the title of chairmen of volunteers.34 Rice and White are reported to have said: "Well, you're the last people who are complaining. What do you want now?" Audrey Billings responded that the Red Cross would lose volunteer support if the volunteers were not treated respectfully. Rice and White told Billings and Toni Busch: "There will always be volunteers." The last of the holdouts detected no fear from chapter officials, and most of the intimidated volunteers ended the insurrection. Many of the White County volunteers, including Hipp, continue to volunteer for the Red Cross, apparently oblivious to the fate of this author and the Paytons who had lost their volunteer careers in the Red Cross as a penalty for fighting the White County volunteers' battle, as they had pleaded for us to do throughout 1995.

PROFESSIONAL, LEGAL, AND ETHICAL ANALYSIS

1. PROFESSIONAL ANALYSIS

The reprisals inflicted on Red Cross volunteers in Northeast Georgia by chapter officials--and, by their sin of omission, officials of the national sector of the American Red Cross--violated the norms and expectations to which volunteer managers are obligated to adhere.

Volunteer rights. The reprisals deprived the volunteers of their rights. Freezing volunteers out of the decision-making process and punishing them for asserting their right to participate in that process violated professional norms for volunteer managers. Ilsley explains that volunteer managers should understand their position to be "that of liaison officer, not drill sergeant." One of the most important jobs of a volunteer manager, he says, is ensuring "that volunteers participate as much as possible in all parts of an organization and that their input is welcomed and utilized."35 The Code of Ethics and Standards, adopted at the annual meeting of the Association for Volunteer Administrators in 1975, established this ethical precept:

The Volunteer Services Administrator shall promote the involvement of persons in decision-making processes which affect them directly.36

When Northeast Georgia Chapter executive director Pamela Watts (1) empowered the White County DAT captain to refuse to hold meetings at which new volunteers would be activated, (2) withheld information and staff support to the new volunteers, and directed her subordinates to do the same, (3) interfered with volunteer coordinator Hipp and her recruits when they planned to serve refreshments at their own personal expense at a DAT meeting, and (4) caused this author and the Paytons to be terminated from the Red Cross volunteer staff, she ran squarely afoul of this standard.

The exclusion of volunteers from decision-making participation is, unfortunately, common in the Red Cross organization, which is dominated by the "management sphere" as opposed to the volunteer component. Ilsley provides this analysis:

The dominant sphere of influence in many modern volunteer organizations appears to be the staff/professional one. This conclusion is based on the observation that the workplace model, which protects professional standards, has become the basis of policy in an increasing number of volunteer organizations. In other organizations, however, especially social and political movements and some agencies within public health volunteer programs, the volunteer sphere predominates. The management sphere is most important in groups such as religious groups, the Master Gardeners program, RSVP, and the American Red Cross.37

Relying on the work of Pearce, Ilsley laments the predominance of the "workplace model." The model "is inappropriate for volunteers" because volunteers, by the nature of their unpaid status, are less dependent on the institution than are paid staff members and, hence, they are less vulnerable to the command-and-control approach. Furthermore, the more professionalized organizations exhibit less "recognition and toleration of different personalities and viewpoints." Ilsley adds:

The ideals of professionalism and of pluralism and democracy inevitably seem to conflict.

Some degree of professionalism is no doubt necessary in most formal volunteer organizations, but managers should never lose sight of the fact that the true strength of voluntarism lies in the forums it provides for involving citizens in public life and keeping our institutions alive and responsive. Making sure that volunteers participate as much as possible in all parts of an organization and that their input is welcomed and utilized is one of the most important parts of a volunteer manager's job, for doing so can produce both deeper volunteer commitment and a more viable, flexible organization.38

In taking punitive measures to quell the rebellion among volunteers in Northeast Georgia, the chapter's management did precisely the opposite in teaching volunteers that there is a price to be paid for attempting to participate in organizational decision-making.

Protecting the agency's mission. The professionalization of the organization to the point that the status and role of volunteers are trivialized can actually undermine the agency's ability to accomplish its mission. One mission is community involvement; the potential for the professionalized organization to thwart volunteers' attempts to be involved in organizational decision-making was discussed in the immediately preceding paragraphs. For another thing, the rigidity of the professionalized organization, in and of itself, can drive volunteers away, depriving the agency of the labor that it needs to accomplish its mission. Ilsley observes:

Routine volunteering for large, well-established formal organizations such as United Way may drop as such organizations become more commonly viewed as hidebound, unresponsive to individuals, and ineffective at solving social problems.39

Another aspect is that the obsession of volunteer managers to professionalize the organization in order to solidify their personal control may distort the organization's understanding of its mission, and a perverse shift in the organization's direction may occur. Ilsley says:

As professionalism spreads in an organization, opportunities for volunteers to change or question procedures on even the mission of the organization decrease. In time, an agency administration's choice of managerial tools will likely define the agency's mission rather than the mission mandating the tools to be used. For example, suppose volunteers at a hospice for people with AIDS tolerated the initial mandatory training, but resented the subsequent mandatory in-service training and expressed their dissatisfaction by refusing to attend those subsequent meetings. To stave off the problem, a manager could screen volunteers from that point forward to ensure compliance in organizational regulations. However, a wiser manager would not permit the rules of the organization to interfere with the quality of service and might instead discuss the matter with volunteers to determine what kind of, or if any, in-service training is warranted. The mission of the hospice, after all, is not to meet standards of volunteer compliance; it is to help [patients with AIDS].40

Thus, when the executive committee of the Northeast Georgia Chapter's Board of Directors decreed that henceforth all volunteers would attend an orientation and sign a written contract, there could be little doubt that the purpose of the orientation and contract was to exact compliance from the Red Cross volunteers, and not to improve service delivery to disaster victims in the chapter's service area.

Citing research by McKnight and Illich, Ilsley observes that their work

supports the contention that professionalized organizations typically lose their usefulness in time because they need more and more time and money to achieve the same goals. This occurs because the organizations allocate increasingly greater amounts of resources to controlling measures such as personnel processes, screening and placement techniques, and elaborate training. In short, by seeking efficiency excessively, such organizations actually become less efficient.

Furthermore, McKnight, presenting the "iatrogenic argument," explains that professions and professionalized organizations not only may become less useful but may actually begin to create the problems they originally intended to solve. Thus courts may "create" injustice and crime, hospitals may cause people to get sick, transportation systems may slow travel, and education programs may cause befuddlement and dependency. As offensive as it sounds, iatrogenic situations arise from an evolutionary process whereby an increasing percentage of the budget is spent on organizational survival and control. . . .

The trend toward professionalism probably does not doom volunteer organizations; the goodwill and independent spirit of volunteers is likely to be too strong for that. This trend certainly has had an impact on voluntarism, however, and on the whole that impact has been a negative one.41

The first casualty, Ilsley says, may be the organization's accountability.

One of the most outstanding pieces of irony in voluntarism today is that the very act of exercising control, especially in ways similar to those used in the workplace, may diminish the possibility of creating a durable or accountable program.

Ilsley contends that volunteer managers can achieve their goals more effectively by allowing the volunteers to control their own activities and "to create their own healthy working and learning environment."42

ARC has been plagued with financial and management problems in recent years, indicating that the policy of national headquarters management to centralize power has been ineffective. In December 1996, the Nonprofit Times suggested that ARC president Elizabeth H. Dole, who was still on leave, resign instead of resuming her post because five years of Dole's presidency had allowed the organization to remain troubled "both financially and managerially."43

Likewise, reports have reached this author that the Northeast Georgia Chapter has found itself in increasingly difficult financial circumstances. Among the results are that victims of single-family fires are receiving enough Red Cross relief assistance to provide them with food, clothing, and shelter for all of two days! While the Red Cross motto is "Help Can't Wait," in Northeast Georgia the help surely runs out very quickly!

2. LEGAL ANALYSIS

Eide reports that the legal rights of volunteers "remain unchanged from what they were in the 1930s and before." He explains that because volunteers do not depend for their livelihoods on the organization that does not pay them anyway, federal and state laws assume that the relationship is consensual and that either party may terminate it. To use a term of labor law, organizations appoint volunteers on an "at-will" basis, and are obligated neither to retain the volunteers nor to provide them with due-process protections before they can be driven away.44 On this basis, volunteers who are considering making a commitment to a volunteer organization--a commitment that may include many hours of training and donated labor--probably ought to think twice before entering into a relationship in which their managers may act with impunity in a heavy-handed way and the volunteers may have no recourse.

However, Eide adds that volunteers are believed to be covered by the Fair Labor Standards Act; the Civil Rights Acts of 1866, 1964, and 1991; the Occupational Health and Safety Act; and the Americans with Disabilities Act. Furthermore, the organization itself may develop contracts, handbooks, and codes that establish rights for volunteers that they would not have in the absence and silence of federal and state laws.45

The American Red Cross has developed elaborate rules and codes purporting to provide rights and opportunities to volunteers. Many volunteers (including this author and the Paytons) have signed Red Cross codes of conduct that establish obligations to which both parties are bound. For example, the American Red Cross Volunteer Handbook published by the National Office of Volunteers includes this code of conduct:

All volunteer and paid staff members of the American Red Cross, in delivering Red Cross services and in all other Red Cross activities, shall meet the following standard of conduct.

No volunteer or paid staff member shall -

a. Authorize the use of or use for the benefit or advantage of any person, the name, emblem, endorsement, services, or property of the American Red Cross.

b. Accept or seek on behalf of any person, any financial advantage or gain of other than nominal value offered as a result of the volunteer or paid staff member's affiliation with the American Red Cross.

c. Publicly utilize any American Red Cross affiliation in connection with the promotion of partisan politics, religious matters, or positions on any issue not in conformity with the official position of the American Red Cross.

d. Disclose any confidential American Red Cross information that is available solely as a result of the volunteer or paid staff member's affiliation with the American Red Cross to any person not authorized to receive such information or use to the disadvantage of the American Red Cross any such confidential information, without the express authorization of the American Red Cross.

e. Knowingly take any action or make any statement intended to influence the conduct of the American Red Cross in such a way as to confer any financial benefit on any person, corporation, or entity in which the individual has a significant interest or affiliation.

f. Operate or act in any manner that is contrary to the best interests of the American Red Cross.

Nowhere in the code of conduct is dissent identified as a cause for termination of the relationship between the volunteer and the organization. Although this author and the Paytons were fully in compliance with this and other Red Cross codes of conduct, the Northeast Georgia Chapter terminated their volunteer status and ARC officials either endorsed the actions of chapter management or looked the other away.

The "termination" letters violated other Red Cross regulations46 and deprived the recipients of due process. Moreover, the "termination" letters were inconsistent with these fundamental principles of the international Red Cross movement:

n HUMANITY -- . . . [The] purpose [of the Red Cross] is to protect life and health and to ensure respect for the human being. It promotes mutual understanding, friendship, cooperation and lasting peace amongst all peoples. . . .

n UNITY -- There can be only one Red Cross society in any one country. It must be open to all. It must carry on its humanitarian work throughout its territory.47

A group that "must be open to all" cannot arbitrarily "terminate" affiliations with itself. The termination notices that chapter Chairman Pope and executive director Pamela Watts issued were ultra vires acts that had no legitimacy.

3. ETHICAL ANALYSIS

The treatment of Red Cross volunteers in Northeast Georgia was unethical and immoral, based on the following criteria.

Manipulation. The disinformation involved when Watts contended that the White County volunteers were self-governing, while she directed her staff to withhold information and staff support to them and interfered in their routine plans to serve refreshments at their own expense at DAT meetings, constitutes manipulation. Sissela Bok says, "Deception . . . can be coercive. When it succeeds, it can give power to the deceiver--power that all who suffer the consequences of lies would not wish to abdicate"48 Oppenheim explains the benefits gained by a deceiver: "Y purposely influences X's activity, but purposely conceals the fact from him. X complies in the mistaken belief that he is acting in his own interest."49 Goodin states:

Power plays are far more successful if accomplished deceptively. You stand a far better chance of getting your way if others do not notice that they should be resisting.50

Had the White County volunteers known from the outset that chapter management intended to dominate decision-making, they could have (1) agreed to the imbalance of power and entered knowingly into the asymmetric relationship or (2) avoided the hours of training, the plethora of calls to recruit volunteers and schedule them for training, and the aggravation that enveloped them as the year 1995 wore on. Instead, the victimized volunteers were drawn into conflict even as the circumstances that were generating the conflict were mysterious. This entire publication would have been unnecessary had all of us been apprised, from the outset, that the role of Red Cross volunteers is to be vassals. One purpose of this publication, in fact, is to alert other Red Cross volunteers and prospective volunteers of the manipulation occasioned by attempts by Red Cross public-relations officials to portray Red Cross volunteerism as an opportunity that ennobles and empowers volunteers, when this case study reveals that the relationship is exploitative.

Treating people as means rather than as "ends." Philosopher Immanuel Kant denounces the use of human beings as "means to an end" rather than as "ends in themselves." Symptomatic is the result of professionalism which causes volunteers to be "treated like interchangeable objects rather than like people with individual interests and abilities." Managers with those point of view "see the success of their organization's programs as lying in their hands; to them, volunteers are simply one element in production."51 When Northeast Georgia Chapter volunteer chairmen Rice and White told the last holdouts of the White County rebellion that "[t]here will always be volunteers" who will help the Red Cross, they were expressing the viewpoint that volunteers are interchangeable objects, because they can be replaced by other willing (unaware) arrivals.

Dignity. A related ethical issue is the deprivation of human dignity. Writing in the last half of the 19th century, Bellamy asserted: "The primary principle of democracy is the worth and dignity of the individual."52

Fisher and Cole summarize the purpose of the guiding principles of the Association for Volunteer Administration this way:

The AVA's guiding principles are based on a commitment to social responsibility, an understanding of the need of every person to express concern for others, and the concepts of dignity and self-determinism.53

The AVA's code of ethics states:

The Volunteer Services Administrator shall develop a volunteer program which will enhance the human dignity of all persons related to it.54