POLICY AND ECONOMICS OF HEALTH CARE

By Barry D.

Friedman, Ph.D.

Copyright 2000 by

Barry D. Friedman -- All Rights Reserved

1. ETHICAL AND PRACTICAL SOURCES OF THE DECISION TO ALLOCATE HEALTH CARE

To how much health care is each individual entitled? If one subscribes to capitalist theory, then, presumably, his answer would be: One has the right to as much health care as she can afford.

There are other approaches, too. One might rely on religious values, and cite, for example, Leviticus 19:16, which says: "You shall not . . . stand idly by the blood of your neighbor." Presumably, this means that all of us are responsible for making sure that the rest of us receive treatment for illnesses and injuries.

One might resolve the matter, instead, by looking at the practicality of the matter. Let's say that society offers people just the amount of health care that they can afford. Of course, some people--poor people--can't afford any. What are the results of having poor, sick people who receive no medical treatment?

» People who carry disease, and are untreated, can help to fuel an epidemic.

» People who are ill and who receive no treatment can become incapacitated, thus becoming unable to carry out any kind of responsibilities to their families and to society. They become a costly burden on their families and on society.

The question of whether people are to be provided health care arises in other decision centers as well. For example, employers often offer access to health care as a fringe benefit that can help the company attract and keep good employees. The company also benefits from employees' shorter periods of illness.

As another example, for elected officials, offering health-care benefits such as Medicare and Medicaid is good politics. Elected officials have discovered, over the years, that "entitlement programs" like Medicare and Medicaid keep the electorate content and improve the proportion of incumbents who are reelected.

A contract or law that makes health care available to a beneficiary creates a "right" to that health care. Of course, a contract can eventually expire. The U. S. Supreme Court allows employers to cut back on the range of benefits that they provide to employees.1 And a law can always be repealed. But, as James Q. Wilson has observed with regard to "entitlement programs": "A benefit, once bestowed, is not easily withdrawn."

The result of many of these fringe benefits and entitlements is the "third-party payer system," in which the patient/beneficiary receives health care from a physician or hospital, and a third party--such as an insurance company or the government--pays for the services that have been rendered. Thus, the cost of the health care is of limited interest to the patient, who doesn't pay for the treatment, and the physician or hospital is gratified most of all by extravagant therapies and costs. This has driven third-party payers to distraction, because the principals--the patient and the health-care provider--lack an incentive to keep costs down, and the third-party payer is left with the duty to obtain enough revenue to pay for the benefits.

To the patient and the health-care provider, one overriding principle of "fairness" prevails. The fundamental rule of fairness is this: "What's fair to someone is that she gets as much as she got last year, plus a little extra." Students of public policy will recognize this as a corollary of the incrementalism model of public policymaking. By this canon, cutbacks in health-care coverage are never fair. Significant expansions in health-care coverage are very fair, but that kind of change constitutes a "windfall" that is unexpected and rarely demanded. The 2000 presidential campaign is an example in which the two major-party candidates have offered a windfall to Medicare patients (i.e., coverage of prescription drugs) in an effort to attract that which intoxicates politicians more than anything else: votes.

2. POLICY ANALYSIS

What determines how much money is invested in health care?

To approach this question, let's focus on just one aspect of the health-care system: ambulance transportation. It is a well-known fact of medicine and public health that patients with serious acute illnesses (e.g., heart attack, stroke) or with serious injuries have the best chance of survival if they arrive at the hospital emergency room within, say, 5 minutes; the probability of survival proceeds to decline as each additional minute elapses. So here we have an independent variable (availability of ambulances) that is easily definable and conceptualized; our dependent variable is survival rates. The inevitable cause-and-effect relationship between the variables is: The more ambulances there are, the fewer deaths that occur. For example, Lumpkin County's Emergency Management Services (EMS) operation possesses three ambulances. The average response time to a call is 6 to 7 minutes--and, as you probably know, the county has a large land area (291 square miles), some of which is mountainous. OK, so think about this for a second: If we want to improve survival rates, all we have to do is . . .

[Try to complete the sentence yourself before you continue to read this essay.]

. . . buy lots more ambulances, hire lots more EMT [emergency medical technician]/drivers for the ambulances, and station the ambulances in the various neighborhoods in the county--a couple in Dahlonega, a couple in Auraria, a couple in Yahoola, and so on. But Lumpkin County DOESN'T DO THIS! The decision not to do deploy all of these extra ambulances DOOMS MORE PEOPLE TO DIE! Why are the elected officials of Lumpkin County, White County, Dawson County, Hall County, Forsyth County, etc., so darned CHEAP? [Try to answer the question yourself before you continue to read this essay.]

The answer is: SCARCE RESOURCES! Society just doesn't have enough resources to attend continuously to every citizen just in case he gets sick or injured. Society COULD, I suppose, vastly increase its investment in the health-care system so that it puts ONE ambulance in every neighborhood and reduces response time to, say, 1 1/2 minutes; maybe we COULD afford THAT. But government's allocation of resources to various programs--a process that we call "public budgeting"--almost inevitably requires that any dramatic increase in one program's budget will come at the expense of another program's budget. Therefore, the dramatic increase in the budget for EMS would come at the expense of--what? Education? Highways and transportation? Publicly operated utility systems? Police and fire protection?

Think of these trade-offs. Say that EMS operations are funded more generously, but other programs that keep the public safe, like police, fire, and highway-maintenance operations, sustain funding cuts. Might this reallocation not result in more deaths? Say that EMS operations are funded more generously, but other programs that keep our society prosperous, like education and transportation, sustain funding cuts. Might our country not go the way of Third World countries, where poverty is the common condition and eventually we wouldn't be able to afford modern health care anyway? Then, what is left of our health-care system would be battling outbreaks of cholera, dysentery, polio, diphtheria, whooping cough, and . . . well, the image is a miserable one.

Instead of making emotional, irrational decisions, we might use some of the methods of public policy analysis to decide how much funding to allocate, as a society, to health care. The premier model of public policy analysis (i.e., the model that offers the best analytical methods and the promise of optimizing the use of resources) is the rationalism (comprehensive) model of public policymaking. Government officials do not usually use the rationalism model to make policy; reliance on the incrementalism model (where this year's policy is the result of small, incremental changes made to last year's policy) is far more prevalent. But one example of the use of the rationalism approach in health-care policy is the development by the U. S. national government in the 1980s of Diagnostic Related Groups (DRGs) as a strategy to cope with the aforementioned "third-party payer" problem. Theretofore, when a hospital treated a Medicare or Medicaid patient, the hospitals would report to the appropriate federal agency its expenses in treating that patient, and the government would reimburse the hospital with a "cost-plus" formula--i.e., the hospital would receive a refund for its expenses plus a surplus percentage. Under this system, the incentive for the hospital was to keep the patient in the hospital for extended periods of time and to subject the patient to as many tests as possible. The government's costs soared. The DRG approach--a comprehensive overhaul of the cost-plus reimbursement system--established fixed reimbursement amounts for each kind of illness. If a patient is brought to the hospital with appendicitis, the DRG schedule determines exactly how much the hospital will be reimbursed for treating the patient, regardless of how the hospital goes about doing it. So the hospital is welcome to keep the patient in the hospital for a month after the appendectomy--but at its own expense! The hospital is welcome to do an MRI or CAT scan on the patient's head, just in case she also has a brain tumor--but at its own expense! And, as you know, hospitals today can't wait to discharge us just about as soon as the surgeons close our incisions. And now, as Paul Harvey would say, you know the rest of the story!

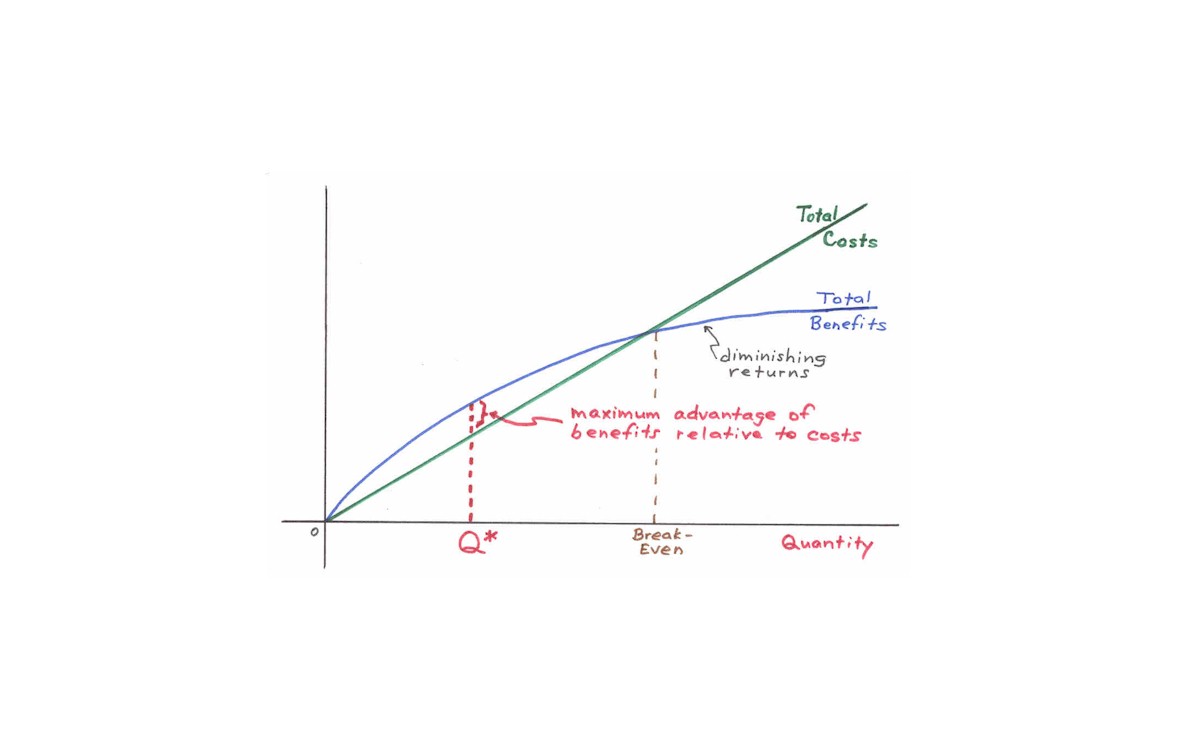

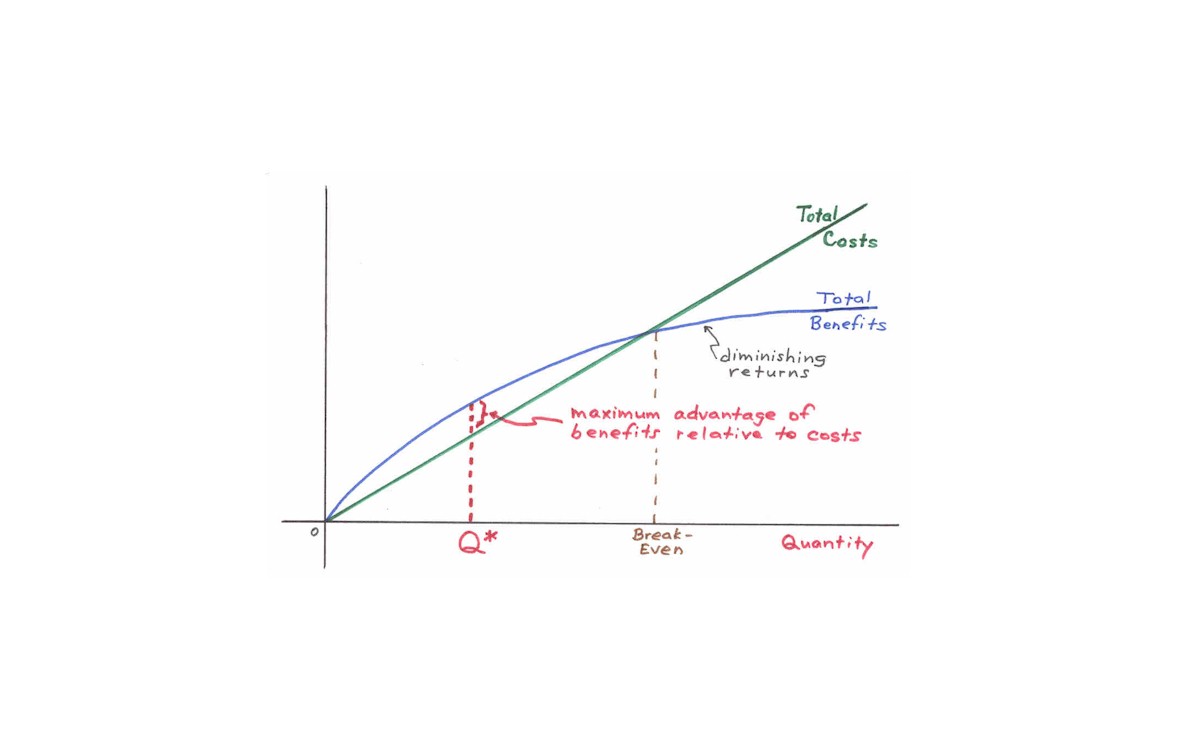

In general terms, the rationalism model is used to bring about maximum efficiency, defined as the best advantage of societal benefits compared to societal costs. Examine this graph:

The value of the independent variable (quantity of units of service), identified on the X-[horizontal-]axis as "Q*", is the point at which the difference between total benefits and total costs is largest (and positive). Therefore, the optimal number of units of service is Q*. One might ask: But why stop at Q*, when still more units of service could still be delivered without sustaining a loss? In fact, this can be done up to the point that the "Total Benefits" and "Total Cost" graphs intersect--the break-even point. Why not continue to deliver service until the break-even point is achieved?

The rationalist's answer is as follows: Instead of delivering more units of service than Q*, why not find some other program that is operating to the left of its value of Q* and invest in that program, until such time as the optimal number of units are delivered and the greatest advantage of benefits compared to costs is achieved. And then, find another program that is operating to the left of its value of Q*--and invest in that program, and by now, you know where this argument is headed. Pigou, a "welfare economist," provided the overall rule for allocating resources to public programs: Invest in the programs, he said, in such a way that every one of them has the same "marginal benefit" as every one of the others. That strategy, he said, will maximize society's return on the resources that it has to invest.

3. THE INCREASING COST OF HEALTH CARE

For many years, the rate of increase in the cost to society of our health-care system has alarmed corporate personnel managers, insurance companies, and government policymakers. These are some of the circumstances that have fueled this unrelenting increase in costs:

» Technology has become increasingly elaborate. The health-care field is an area which has shown an insatiable appetite for newer, more elaborate, and--of course--more expensive technology. Any self-respecting person who goes to the hospital for an ingrown toenail wants to be certain that the hospital can provide him with world-class treatment in case he has a coronary while being treated for the toenail situation. As a result, a person who goes to the hospital for treatment of the ingrown toenail walks off with a bill of $500, because someone has to pay for the costs of the world-class intensive coronary unit.

» Unnecessary medical tests are routine. Physicians and hospitals tend to carry out more medical tests than the immediate symptoms call for, for various reasons. One reason is that the equipment to carry out the tests is there. Another reason is the fear of malpractice suits. "Do you mean that my client, who was being treated for acne, was in a hospital that had equipment that could have detected her intestinal polyp--and you didn't do the test?"

» The American Medical Association, not to mention the American Hospital Association, is extremely effective at lobbying. If elected officials and other government policymakers are intimidated by anyone, they are intimidated by physicians. Every so often, each government official goes to a physician, takes his or her clothes off, and has his prostate palpated, or her uterus probed. There is something mysterious about physicians who have such unique access to our bodies, and who cure us when we feel that we are about to die.

» The third-party payer system continues to cause increasing costs. Insurance companies have yet to resolve this problem with finality.

Any discussion about the increasing cost of health care must include a reference to the astronomical costs associated with the typical person's last year of life. It is entirely possible that the last year of a person's life may account for 60 or 70 percent of her lifetime health-care costs. Some of these expenditures are used to keep a nearly dead person breathing and her heart pumping, for any number of reasons that include the fear of being prosecuted for murdering the patient if extraordinary measures are not used. In this regard, one might mention the very small proportion of citizens who have a living will. The irony is that these resources are being dedicated to keeping dying people "alive," while many indigent children have difficult getting access to vaccinations and immunizations that could prolong their lives by many decades in many cases.

4. OBLIGATIONS OF A HEALTH-CARE PROVIDER

Finally, I turn to the matter of what obligations a health-care provider has to her patients. The principal obligations are as follows:

» As the Hippocratic Oath states, the health-care provider is obligated to, "first, do no harm."

» The health-care provider is obligated to provide honest information to his patient.

» Every health-care provider is ethically obligated to refrain from the practice of discrimination in her practice of nursing or medicine.

» The health-care provider is obligated to ensure the protection of innocent bystanders.

» The health-care provider is obligated to provide performance in exchange for payment.

A newly trained and certified health-care provider might also ask herself this question: "Am I responsible to treat needy patients, who can't afford health care, for free?" The question can be restated in this coldly analytical way: "Does a health-care professional have an obligation to make up for all of the inequities of the capitalist system?"

These are not easy questions to answer. There are biographies available that tell about the lives of physicians and nurses who dedicated their lives to healing and nursing indigents in this country and other--especially Third-World--countries, and their actions were indisputably heroic. On the other hand, one can legitimately take notice of other ethical duties that people have that may compete with the duty to serve indigents on a pro bono basis. For example:

» The health-care professional has a duty to support himself and his dependents. It is an altogether decent and socially laudable thing to do to get married and have children, and then to support them! To undermine one's ability to make a living by exclusively providing pro bono services would violate the ethical responsibility to avoid becoming a burden on society himself, and to avoid turning his wife and children into dependents on the state's welfare system.

» The health-care professional has a duty to provide a stable livelihood to her employees. If, by exclusively providing pro bono services to indigent patients, the health-care provider cannot provide a steady source of pay and benefits to employees, she is disregarding her ethical duty to those who are legitimately dependent upon her for their support and the support of their families.

» The health-care professional has a duty to have a constructive outlook and to be civil to others. Continuously and exclusively treating patients who are not paying for their own health care can lead to a very cranky physician or nurse and, ultimately, premature burn-out.

Therefore, a new health-care professional may, ethically, look for a reasonable balance between providing remunerative services and, on occasion, providing charitable services, without thinking that he has failed to display a concern for the welfare of others.

FOOTNOTE

1 An employee who possessed health insurance provided by his employer was diagnosed as having the HIV virus. The employer revoked the employee's insurance coverage. The U. S. Supreme Court decided in favor of the employer. The employee was left uninsured.

Personal disclaimer: This page is not a publication of North Georgia College & State University and NGCSU has not edited or examined the content of the page. The author of the page is solely responsible for the content.

Last updated on July 28, 2004, by Barry D. Friedman.

Visit Barry Friedman's home page . . .