OPTIONS IN TEACHING

REAL STUDENTS ABOUT REAL LIFE:

A Discussion About Pedagogy

By H. Gibbs Knotts,

C. Don Livingston, and Gordon E. Mercer, Western Carolina University,

and Barry D. Friedman, North

Georgia College & State University

Copyright © 2003 by H. Gibbs Knotts, C. Don Livingston, and Gordon E. Mercer.

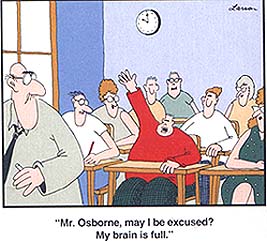

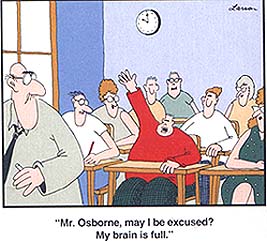

TRENDS IN PEDAGOGY

Throughout the 20th century and into the 21st century, the protocol for teaching students from junior high school to graduate school involves chair/desk units arrayed in columns and rows and occupied by students who, just last night, read the next chapter of the textbook and who now listen to a teacher’s lecture and take notes. This "technology" is probably as effective as anything else for the memorization of large quantities of facts. It is arguably much more efficient to tell students that water boils at 212 degrees F than it is to set up a stove and a thermometer and observe what happens when the temperature of the water on the stove reaches 212 degrees F.

Critics of the traditional method offer numerous complaints about it: (1) The facts that students memorize in this fashion usually do not remain in their memories for long. (If the students are lucky, the facts will stay in their memories until the examination is over. If the students are not lucky in that way, they will be remembered as poor students.) (2) The accomplishment of memorizing facts does not necessarily advance to the ability to do anything with those facts. (3) The knowledge of facts may be substantially separate from what the implications of the facts look like. It is one thing to tell a medical student what a gangrenous liver looks like; it is another thing entirely to cause the medical student to dissect an actual gangrenous liver and observe its appearance. (4) This technology trains students to be independent actors in the learning process. The notions of "working together" and "working cooperatively" will long since have been denounced as methods of cheating. Accordingly, students are not trained to work with others, which can be problematic when the students enter an employment setting where cooperation is necessary for success.

The authors of this essay are concerned about the efficacy of the methodology of reading the textbook, hearing a lecture, and taking notes for the purpose of teaching students about government, politics, and citizenship. It is entirely possible for students to earn a college degree in political science without ever having seen a state legislature or a city council meet for the purpose of enacting state laws or local ordinances. It is entirely possible for students to earn that degree without ever having seen a political-party convention meet for the purpose of electing party officers or selecting the party’s nominees in the next general election. It is entirely possible for students to earn that degree without ever attending a political rally. The nuances of how actors in the political arena talk to one another, bargain with one another, and use rhetoric disingenuously to avert unwanted attention and controversy will almost never be explained in a book or a lecture—or even if they are, who would be moved by the description?—but are observable in a real political event.

The reasons for sticking stubbornly to the textbook/lecture approach are heard frequently enough. Teachers are overworked already, and do not have any appetite for the additional obligation of organizing field trips during the school day. Such field trips may also interfere with the students’ attendance in their other classes, and meet with protest from their other instructors. Students’ schedules outside of the school day are overstuffed with part-time jobs, involvement in sports, attendance in after-school church classes, obligations at home (such as chores or babysitting for siblings), and other responsibilities; assignments to go to a city-council meeting in the evening may be met with a chorus of protests from the students and their parents.

A few years ago, co-author Friedman taught his university’s course entitled "Senior Seminar in Political Science." He required each student to attend at least one political-party event and at least one official governmental meeting. He braced himself for resistance, but was relieved to notice that the students were cooperating to schedule a trip to Georgia’s state capitol. At that point, he offered to reserve one of the university’s shuttle vans; on the agreed-upon day, about 10 juniors and seniors majoring in political science at North Georgia College & State University traveled with him to Atlanta and observed the state’s House of Representatives debating a hotly controversial hate-crimes bill. He was gratified to read the essays that the students submitted after returning from their visit to the General Assembly.

HOW THE

TRADITIONAL TEACHING/LEARNING METHOD

RESEMBLES SOCIETY’S SEPARATENESS

Social scientists and journalists have recently lamented the decline of civic engagement in the United States (Putnam 1995; Mann 2000). The Monica Lewinsky scandal is an example of a prominent event that increases cynicism and apathy, especially among younger Americans.

Should social scientists remain idle as civic bonds deteriorate? How can social scientists address the issue of civic engagement? Without question, the causes and consequences of civic engagement should be examined using rigorous empirical analysis. Researchers should monitor the level of engagement and examine the factors determining engagement in society. Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville noted the strength of civil society in 19th-century America, and more recently Robert Putnam has written about the growing propensity to "bowl alone" in the United States (Putnam 1995; Putnam 2000). Many studies have linked levels of civic engagement, such as voter turnout, to socioeconomic factors (Wolfinger and Rosenstone 1980; Piven and Cloward 1988).

Aside from empirical analysis, social-science professors may choose to address the question of engagement in the classroom. Civic participation can be a topic covered in courses, and assignments can require students to participate in the political process. Social-science courses may also include a service-learning component to foster civic activism. Beyond the classroom, colleges and universities continue to develop missions that reach beyond the quadrangle. Many institutions have created offices of university/community partnerships to coordinate outreach activities.

WESTERN NORTH CAROLINA’S LOCAL GOVERNMENT YOUTH ASSEMBLY

A group at Western Carolina University in Cullowhee, N. C., directed by the university’s Public Policy Institute, developed an effort to foster civic engagement among middle- and high-school students. They planned and implemented a regionally based Local Government Youth Assembly, an event where over 200 students set aside a Saturday to debate and approve simulated legislation on local and regional public policy issues.

Co-author Mercer directs the Public Policy Institute, in addition to serving as associate dean of graduate studies and advisor of the university’s Pi Gamma Mu chapter. Also serving on his committee were co-author Livingston, who is associate dean of arts and sciences and another Pi Gamma Mu advisor, and co-author Knotts, who is director of the university’s Master of Public Administration Program. Dr. Mickey Duvall, associate director of the Public Policy Institute and another Pi Gamma Mu advisor, also served on the committee.

The Pi Gamma Mu chapter contributed several volunteers as organizers of the

event. Robert Blankenship, chapter president, and Daran Dodd, Michael Hancock,

Alecia Trynor, all vice presidents, participated. Other student volunteers were

Sharon Butterfield, Felicia Hogue, Kristen Hove, and Amanda Jones.

The Planning Stages

The first step in the planning process was to secure funding for the youth assembly. Grants covered expenses for meals and refreshments at the youth assembly, as well as the costs of photocopying, long-distance telephone calls, travel to local schools, and videotaping the event. A generous donation from the Horowitz Foundation subsidized many of the expenses for the project.

In addition to receiving financial support, organizers enlisted the region’s largest newspaper, the Asheville Citizen Times, as a partner. The backing of the newspaper signaled the significance of the conference and made it easier to recruit speakers from within the government of the City of Asheville, which was also a co-sponsor of the event. Support from the region’s largest newspaper also provided invaluable media coverage before and after the event.

Developing an agenda for the event also required considerable planning. Organizers began the assembly with speeches from local elected and administrative officials. Following the speeches, students would meet in committees to debate legislative proposals. Committee members would discuss and amend proposals and eventually submit legislation to the entire assembly.

Rather than form committees on the day of the assembly, organizers talked with local community leaders about key problems in the region. Many of the leaders faced similar policy challenges, and, as a result, six logical committee areas emerged: Cultural and Heritage Tourism, Economics, Education, Environment, Health and Human Services, and Planning.

Organizers encouraged conference participants to prepare legislation in advance of the assembly. Participants were sent legislative proposal guidelines that prompted students for the name of the legislation, purposes of the legislation, problems in implementing the legislation, and cost estimates. Students were encouraged to contact local-government officials for help drafting their legislative proposals.

Another important step in the planning process was the enlistment of undergraduate and graduate students to participate in the youth assembly. College students recruited participants by telephoning and visiting local middle- and high-school classrooms. When possible, college students visited the high schools from which they graduated to encourage assembly participation. On the day of the assembly, college-student volunteers coordinated registration efforts and chaired legislative committees.

Perhaps the most time consuming aspect of planning the youth assembly were the steps required to guarantee an adequate level of attendance. Organizers recruited participants from the 13-county region and established a goal of attracting 200 students. The crucial element in the recruitment process was the involvement of middle- and high-school teachers. In the early stages, organizers contacted school principals instead of teachers. Although principals expressed interest in the assembly, it was difficult to gauge the degree of commitment. Once organizers began working with teachers, participation increased and became more solidified. When possible, teachers were encouraged to attend the event with their students.

Finally, once teachers committed to bringing a group of students, organizers

maintained contact by sending out conference updates including committee lists

and samples of possible legislation. In addition, when the local newspaper

printed an article highlighting the upcoming assembly, teachers received a copy

of the article along with a reminder of the upcoming event.

The Youth Assembly Convenes

The Local Government Youth Assembly convened at 9 a.m. with opening remarks and recognition of participating teachers. Six speakers addressed the youth assembly in two 45-minute segments. The first group of speakers consisted of a city manager, a police chief, and a county commissioner. After a 15-minute break, a county commissioner from a different county, a county-commission chair, and the president and publisher of the sponsoring newspaper spoke to assembly participants. Some speakers opened the floor to student questions, providing a lively exchange of ideas.

Following the second group of speakers, students met in committees to consider legislation to be submitted to the entire assembly. Many students arrived with detailed legislation and used this time to cultivate support for existing proposals. Other students brought basic recommendations and worked to refine their proposals for presentation during the afternoon session. Students joined one of six legislation committees: education, environment, planning, economics, tourism, and health. The education and environmental committees were the most popular. Graduate students served as committee chairs and worked with participants to consolidate similar proposals and determine support for proposals. Each committee voted on whether to submit several bills for consideration by the entire assembly.

During lunch, boxed meals were provided and students remained in committees to hear the keynote address from a mayor. Following the mayor’s remarks, a Gamelan Group entertained the assembly with Indonesian music. An impromptu civic protest occurred after lunch when students voiced concerns that there were no recycling containers for aluminum cans. Students from the Environmental Committee created a makeshift recycling station and carried the cans home at the end of the event.

One of the liveliest components of the assembly was the 30-minute legislative-lobby session. Students moved throughout the room lobbying other delegates in an effort to gain support for their legislation. In anticipation of the lobbying session, several students distributed flyers in support of their legislative proposals.

After lunch, students began formal consideration of legislation. Two individuals shared responsibility for presiding over the legislative session. The presiding officer, on a rotating basis, asked members of each committee to step forward. Delegates had been identified during the morning session and assigned responsibility for introducing, discussing the significance of, and responding to questions about specific proposals that had been reported out of their respective committees and placed on the afternoon’s legislative agenda. To get a large numbers of bills considered and acted upon in a relatively short period of time, the presiding officers had to keep an eye on the clock and monitor the situation closely. Following debate, students voted yes or no on each bill.

Overall, the youth assembly considered 25 pieces of legislation. Environmental legislation dominated the assembly and included proposals on clean air, solar energy, mandatory recycling at high schools, and mountain-bike-trail maintenance. Several education proposals emerged, including legislation to fund school resource officers, a magnet school for technology, teacher recruitment and retention, and a state lottery for education. To encourage tourism in the region, the assembly voted to create a board of tourism for Western North Carolina as well as a new civic center to host regional events. Economic development proposals included efforts to protect small businesses in the region as well as the promotion of technology-based industries. Health and human-service legislation focused on affordable housing and the licensing of homeopathic medical practices.

At the conclusion of the assembly, students were given refreshments and certificates of participation, and asked to complete a survey on the Local Government Youth Assembly as well as other public-policy issues. Results from the survey were used to write editorials on the "op-ed" page for the region’s newspaper about the political attitudes of local youth: Two of the op-ed articles were written by co-authors Knotts and Mercer; a third op-ed piece was written by co-author Knotts and Mickey Duvall.

Evaluation

By most accounts, the Local Government Youth Assembly was a success. The local television news station sent reporters to cover the assembly and the regional newspaper published several articles about the event. The newspaper printed an editorial urging youths to continue their interest in public policy, and summarizing the legislation approved by assembly participants.

Student feedback was overwhelmingly positive as well. In an evaluation of the assembly, over 95 percent of students believed that the youth assembly was a needed event. Following the assembly, several students lobbied local-government officials on behalf of their legislation and one student group made a formal presentation to a local school board.

Teachers also responded positively to the youth assembly. Many teachers used the opportunity to network with other educators and exchange ideas on fostering community activism among students. As another testament to the success of the assembly, several teachers organized smaller-scale youth assemblies in their classes following the event.

For future youth assemblies, it might be beneficial to enlist fewer speakers and encourage more question-and-answer time between speakers and students. Several youths indicated, that while they enjoyed the speakers, they wanted to begin debating proposed legislation earlier in the day. In addition, a smaller number of students may enhance the quality of debate and increase the overall level of participation. If the youth assembly does include several hundred participants, it is important to create smaller committees. Lastly, eight hours is a long event. With fewer speakers and fewer student participants, a half-day would be enough time for future events.

Perhaps most importantly, the Local Government Youth Assembly provided encouraging signs for the future. Over 200 middle- and high-school students gave up an entire Saturday to talk about politics. Even more impressive, the level of debate rivaled what might have been found in county courthouses and city halls throughout the region.

CONCLUSION

The continued use of the textbook/lecture method will deliver the same results to which communities have become accustomed for decades. Students certainly learn something from that method; whether what they learn is adequate for them to become active in political and community life is debatable. The authors believe that observation of real events and participation in—if not real events—at least simulations like the Local Government Youth Assembly and similar reproductions will create citizens who are actually prepared, by virtue of having realistic models in their minds, to jump in to politics, associations, and other instruments of public policy and community activity.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

H. Gibbs Knotts is an assistant professor in the department of political science and public affairs at Western Carolina University.

C. Don Livingston is associate dean of the college of arts and sciences at Western Carolina University.

Gordon E. Mercer is a professor in the department of political science and public affairs at Western Carolina University and director of the Public Policy Institute.

Barry D. Friedman is professor of political science and coordinator of the Master of Public Administration Program at North Georgia College & State University.

REFERENCES

Knotts, H. Gibbs. 2000. "Social Capital and Community Development Corporations: Vehicles for Neighborhood Investment." Ph.D. dissertation, Emory University.

Mann, Judy. 2000. "When We Fail to Vote, Democracy Loses." The Washington Post. 8 November 2000, C17.

Piven, Frances Fox and Richard A. Cloward. 1988. Why Americans Don't Vote. New York: Pantheon Books.

Putnam, Robert. 1993. Making Democracy Work. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, Robert. 1995. "Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital." Journal of Democracy. 6(1): 65-78

Putnam, Robert. 2001. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Wolfinger, Raymond E. and Steven J. Rosenstone. 1980. Who Votes? New Haven: Yale University Press.

Personal disclaimer: This page is not a publication of North Georgia College & State University and NGCSU has not edited or examined the content of the page. The authors of the page are solely responsible for the content.

Last updated on July 28, 2004, by Barry D. Friedman.