THE SELF-CENTERED BEHAVIOR OF MANY CHARITY EXECUTIVES

By Barry D. Friedman, Ph.D.

Professor of Political Science

University of North Georgia

Copyright © 2019 by Barry D. Friedman

RELENTLESS BEGGING FOR DONATIONS

Let’s say that you receive in the mail a solicitation for a donation for a charity, and you put a $25 check in the business-reply envelope and mail it to the charity. Is the charity satisfied? Of course not! The charity will suspect that you might own other money, and it will want that, too. You can expect to receive another solicitation from the charity within a few weeks. If you send more money in response to that solicitation, then a fund-raiser for that charity may call you before too long, get you to admit that you have $500 in your checking account, and persuade you to send that $500 to him. Is the charity satisfied now? Well, the charity might be mollified for the time being. But, in a few months or a year from now, the charity will suspect that you have replenished your supply of money, and will want the next installment. The fund-raiser might call you again and suggest that, for your and the charity’s mutual convenience, you should give him your bank-account number or credit-card number and authorize the charity to dip into the account for $50 a month thereinafter. If you donate some more, the charity may eventually propose to you that you include in your will a bequest to the charity. In other words, the charity won’t be finished with you until you are dead.

In his 1979 book Charity U. S. A., Carl Bakal wrote (p. 211):

“So ubiquitous is the Red Cross presence, particularly in connection with fund-raising, that it is easy to believe the probably apocryphal story of the mountaineers stranded for days on some Alp who, upon seeing a Red Cross-armbanded rescue party approach, instinctively waved it away, shouting, ‘We gave!’”

But charity fund-raisers understand that, to establish the continuing relationship that I described above, they need to cause donors to feel good about having donated. What would cause this good feeling? Well, let’s say that a donor would like to enhance her social status. Many people would like enhancement of their social status. So a donor might feel good about having donated to a charity that appears to be successful and supported by influential people.

I contend that successful, well-funded charities design their publicity and fund-raising efforts to impress prospective donors and reinforce the behavior of those who have donated by giving the appearance of being successful, professional, influential, well-connected, energetic, and prestigious. Grobman (2015, pp. 247‑255) lists communication tools that nonprofit organizations use for their communications. The tools include organizational brochures, print and electronic newsletters, news releases, public service announcements (PSAs), and Web sites. A slogan that became popular in recent years is “Go big or go home!” If a charity wants to be successful, these communication instruments must be slick, capture the attention of prospective donors, and reassure those who have donated that they made a clever, status-elevating decision when they donated. The charity’s Web site certainly must reflect the charity’s mastery and dominance of the arena in which it operates. You know what young people think about Web sites that have limited content, are not very functional, and are difficult to navigate. A poorly designed Web site gives a charity the scent of failure and inferiority. People want to be winners and they prefer to associate with winners.

You will not be surprised when I tell you that I have little faith in the accuracy of the content of charities’ communications. Charity publicists and fund-raisers are paid to manipulate the public, and the more persuasive they are, the more pay they will draw. They are certainly not paid to be scrupulously honest. Charities take advantage of Americans’ gullibility and depend on us not to check on their claims and, when the charities are caught doing scandalous things, to forget about them.

In my conference paper, “Nonprofit Organizations and the News Media: Their Mutually Beneficial Relationships vs. the Public’s Right to Know,” I argue that news-media outlets aid and abet charities by puffing them up on their news pages and during their news broadcasts and printing and airing their PSAs at no charge. At the extreme, the news-media outlets get their own editors, writers, and on-air talent to solicit donations from readers, listeners, and viewers. In my opinion, these news-media outlets exaggerate the purity of the charities’ operatives and‑‑what is even worse‑‑understate charities’ misconduct.

Here is a case in point. After the 9/11 atrocity, the American Red Cross fund-raising machine went into overdrive. Television stations begged for donations during their news broadcasts and aired PSA after PSA. Sympathetic Americans were responding by giving millions of dollars. Some of my students asked me what I thought about the Red Cross fund-raising campaign. I replied that the role of the Red Cross in disaster relief is to give people food and clothing if their food and clothing were destroyed and to help them get their residences habitable again. I said that I didn’t think that the 3000 people who died in the World Trade Center needed food, clothing, and shelter. What happened next was entirely predictable. U. S. Sen. Charles E. Grassley (R‑Iowa), chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, began to criticize the ARC for misleading the public and raising donations in the name of 9/11 victims while it fully intended to use the money for other purposes. Even the shameless Red Cross PR operation could not refute the criticisms. I was watching an Atlanta television station’s news broadcast, as the news anchors reported this sordid tale. The broadcast then paused for an advertising break, at which point the station aired a Red Cross PSA asking for donations for the 9/11 victims. If I were making this up, one could certainly dispute my argument. Sadly, my account is true and it’s typical, and it explains how so much wealth is redistributed from compassionate hardworking Americans to overpaid nonprofit fund-raisers, executives, and other operatives.

TAKING ADVANTAGE OF GULLIBLE AMERICANS

In 1987, President Ronald Reagan negotiated the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty with his USSR counterpart, Mikhail Gorbachev. Reagan was asked about the basis on which he was willing to assume Soviet compliance with the treaty. Reagan did not transmit a Tweet denouncing the reporter who asked the question as a “lightweight” or calling Gorbachev a “loser.” Instead, Reagan recited the English translation of a Russian proverb. “Trust, but verify,” he intoned. The U. S. government would not simply trust the Soviet regime to act in good faith. Instead, our government would monitor the Soviet leaders’ conduct and respond accordingly.

It is typical American behavior to trust charities implicitly and to donate without asking questions about the motivations of the charities’ managers. In his 1979 book, Charity U. S. A., Carl Bakal reflected on the gullibility of Americans who, in studies conducted by newspapers and researchers, have been found to contribute willingly to a “Heroin Fund for Addicts,” an “American Communist Refugee Fund,” a “National Society for Twinkletoed Children,” a fund to “Help Buy Rustproof Switchblades for Juvenile Delinquents,” a “National Growth Foundation for African Pygmies,” and a “Fund for the Widow of the Unknown Soldier” (pp. 289‑290).

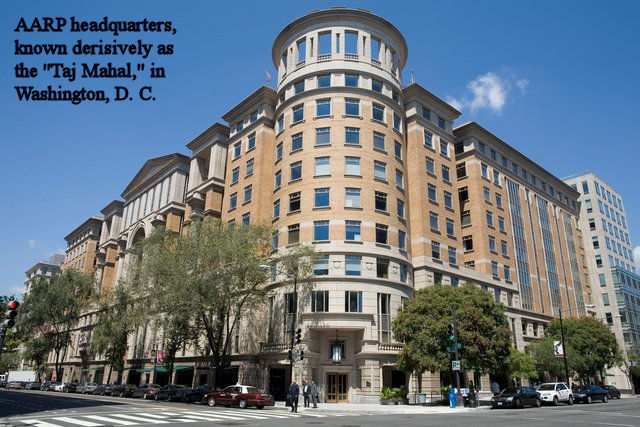

James T. Bennett and Thomas J. DiLorenzo (1994) tell a riveting story about the fund-raising practices of the American Cancer Society, the American Heart Association, and the American Lung Association in their book Unhealthy Charities: Hazardous to Your Health and Wealth. They explain how the three health charities generate surpluses year after year and have on reserve liquid assets amounting to one or more years’ gross revenues. Meanwhile, the charities’ fund-raising solicitations implore prospective donors to send in their donations right away because patients desperately need the charities’ services. Bennett and DiLorenzo ask an intriguing question: If there are patients in urgent need of assistance, why do the organizations stockpile liquid assets amounting to years’ worth of gross revenues? Wouldn’t that be callous and cruel? The authors then explain what the charities’ executives are squirreling away the money for: They plan to build more imposing buildings that will stand as eternal memorials to themselves. These imposing buildings contain elegant office space for the executives. This is an astonishing chronicle of “slack,” to which I refer below.

Roberto Michels’ “Iron Law of Oligarchy” pertains to nonprofit organizations, most of which operate as oligarchies. It is safe to say that all large nonprofits operate as oligarchies. These oligarchical organizations tend to serve as instruments of elite privilege. Let’s say that a population of affluent individuals in a large city donates money to a symphony orchestra. When these donors donate, they deduct the amount of these donations from their amount of income that is taxable. Thus, the government receives less tax revenue from them‑‑revenue that it could have used for social-service programs for disadvantaged people. Who benefit from the symphony? Typically, the audience of symphonic performances consists of affluent people. Not too many homeless individuals show up to hear a concert at symphony hall. Now consider this situation: Harvard University has an endowment fund whose investments total some $36 billion. When an affluent alumna of Harvard donates $10,000, her tax liability may decline by some $4000‑‑$4000 that the government cannot use to alleviate inequity and poverty. Little about the structure of the nonprofit sector gives us any reason to believe that the existence of nonprofit organizations serves the purpose of redistributing wealth from rich to poor and alleviating the suffering of society’s neediest people.

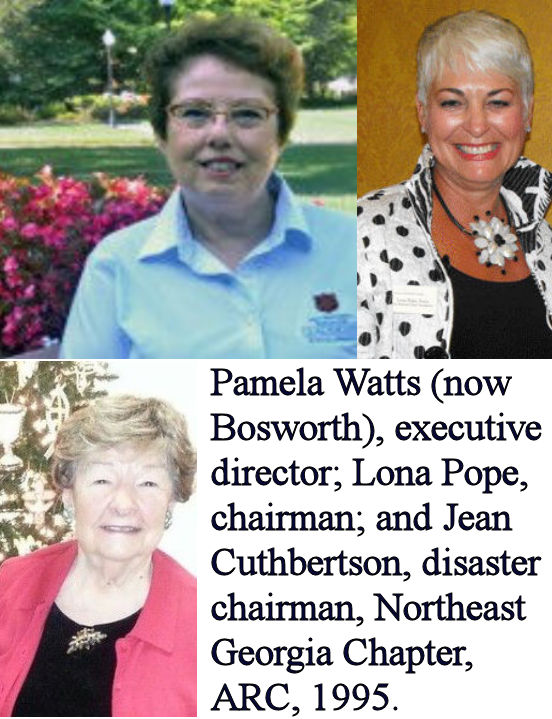

In my case study, “Cracking Down on Red Cross Volunteers: How American Red Cross Officials Crushed an Insurrection by Agitated, Mistreated Volunteers in Northeast Georgia,” I describe an incident in which new disaster-relief volunteers in White County, Ga., struggled to become productive and disaster-ready while the executive director and some board members conspired to deprive them of access to such resources as staff support. (A major purpose of a charity’s paid staff is to provide information and other resources that enable the volunteers to do what they are supposed to do.) When these volunteers and I (the volunteer responsible for arranging for their training) became aware of the conspiracy and protested it, the board cracked down on us and terminated the volunteer status of three individuals, including me. Our appeals to the state, regional, and national levels of the ARC caused the leadership to circle the wagons and stymie our efforts by putting in place a veil of secrecy. The dignitaries on the chapter board‑‑business owners, bankers, lawyers, etc.‑‑could not identify with the field volunteers, who aspired to donate a lot more of their volunteer labor than the dignitaries were prepared to give. Threatened by the volunteers’ desire to be active and to participate in decision-making and disaster planning, the executive director, chairman of the board, members of the executive committee, and other board members preferred to insult, browbeat, frustrate, and chase away the volunteers and perpetuate the chapter’s pathetically insufficient disaster-relief force. When two of the volunteers were invited to meet with the two board members whose title was “chairmen of volunteers,” and stated that the disrespect for volunteers would leave the chapter bereft of sufficient volunteer participation to cope with the needs of disaster relief, the board members replied contemptuously, “There will always be volunteers.” That is to say, the Red Cross will always be able to attract new suckers who assume that the organizers will relate to them in good faith. Once again, perfect information is hard to come by. We volunteers in Northeast Georgia are certainly not the only ones to offer our volunteer labor and find ourselves the targets of mean-spiritedness. There are former Red Cross volunteers all over the United States who describe the same kind of experience. I offer these two observations:

And that’s how much ethics you will tend to find when you enter the offices of nonprofit organizations.

SOCIETY'S EXPECTATIONS VS. SELF-INTEREST-ORIENTED BEHAVIOR

In the United States, the national and state governments bestow impressive benefits on nonprofit organizations. The governments’ expectations are that the organizations will serve the public interest. This will happen as long as those who carry out the organizations’ processes direct their efforts toward accomplishing the organizations’ missions.

The people who operate nonprofit organizations are, alas, human beings, and human beings sometimes give in to their selfish motivations. When operatives in an organization focus their efforts on serving their own interests rather than on accomplishing the organization’s mission, what they are doing is described as “goal displacement.” Goal displacement may be manifested in such practices as delivering services to clients in locations and at times that are convenient for employees but inconvenient for or inaccessible to the clients. Another manifestation would be an unnecessary “business trip” to Denver.

In his 1978 book The Economics of Medical Care: A Policy Perspective, Joseph P. Newhouse defined slack as “an expenditure that management desires for its own sake or privilege; extra thick carpets in the administrator’s office are an example” (p. 69). In the for-profit sector, in a truly competitive environment, plush carpeting should be unaffordable because, forced to charge no more than the competitive price for its products, the firm would have to operate in a “lean and mean” manner. Given this assumption, the existence of plush carpeting must be a symptom of an example of market failure that Newhouse calls “slack.” Where, then, would slack such as plush carpeting be possible? It would be possible in the office of a monopolist, who has succeeded in overcoming market competition, or of a government agency or nonprofit organization that does not confront the furious marketplace competition faced by, say, the bakers of Sunbeam bread.

Literature about nonprofit management advocates that nonprofit operatives fight off the temptation of goal displacement and forgo the opportunity to take advantage of slack. Tschirhart and Bielefeld (2012, pp. 25‑26) write:

“Nonprofit leaders can foster organizational cultures that reinforce ethical behavior. One of the most influential methods may be to use values-based leadership. Top leaders can be role models for ethical behaviors and ensure that key values are infused into organizational policies and practices. Thomas Jeavons suggests that there are five core attributes of ethical nonprofit managers: integrity, openness, accountability, service, and charity. By personally demonstrating these attributes, leaders set the tone for the rest of the organization. . . .

“If leaders reflect these values, and encourage others in their organizations to do the same, they can build and maintain trust in their nonprofits and demonstrate a strong commitment to ethics.”

You can find countless books and journal articles that describe ethical principles that apply to businesses, government agencies, and nonprofit organizations, respectively. As you study them, you might jump to the conclusion that businesses, government agencies, and nonprofit organizations actually behave in accordance with the ethical principles described in those publications. My observations and experience suggest otherwise.

Selfish behavior is constrained, of course, by laws that criminalize certain unethical behaviors. Therefore, a nonprofit organization’s treasurer might refrain from instructing the bank to transfer $25,000 from the organization’s checking account to his own checking account. But he might persuade the executive director to authorize the two of them to take an unnecessary “business trip” to Denver.

Here is a case in point. On August 29, 2005, Hurricane Katrina made its second landfall at Buras‑Triumph, La. The storm flooded New Orleans and caused more than $100 billion in damage along the Gulf Coast. On April 18, 2007, the Board of Governors of the American Red Cross appointed former IRS Commissioner Mark W. Everson as president of the organization. Shortly after his appointment, Everson made his first visit to oversee the ARC’s disaster-relief operation in the afflicted area. The visit was such a success and Everson was so fascinated by what he saw, apparently, that Everson proceeded to make trip after trip to the region. It seems that on his first or second trip he made the acquaintance of Paige Roberts, executive director of the ARC’s Southeast Mississippi Chapter, who was formerly a news anchor for WLOX, the ABC Television Network affiliate in Biloxi, Miss., and they developed a close working relationship. This relationship appears to have been the root cause of Everson’s need to make repeated “business trips” to the Gulf Coast to check on the ARC’s progress in the Katrina relief effort. In fact, in late October 2007, Everson traveled to San Bernardino, Calif., where wildfires were burning, and Roberts accompanied him on the “business trip.” Six months after Everson’s appointment, his top aides alerted the ARC’s Board of Governors that Everson, married to President George W. Bush’s chief ethics counsel Nanette, and Roberts, married to Gautier, Miss., Municipal Court Judge Gary L. Roberts, were carrying on a torrid affair. By then, Roberts was visibly pregnant. The board quickly arranged a conference-call meeting, during which Everson confessed to the affair and resigned. And that seems to be the end of the story. If Everson ever paid the ARC back for his travel expenses to repeatedly rendezvous with his mistress, I have no evidence of it. As far as the financial resources provided by donors and consumed in Everson’s affair: easy come, easy go. As usual, the IRS has nothing to say about this and other irregularities.

SECRECY VS. TRANSPARENCY

I contend that the perpetuation of corruption is the product of secrecy. Nonprofit operatives who are benefiting personally from organization resources depend on secrecy. Under the cover of secrecy, those who practice corruption are not subject to the pressures of stakeholders who might otherwise intervene in the misconduct. One might wonder why a nonprofit organization needs secrecy. Perhaps there are personnel matters that require secrecy. Perhaps there are pending real-estate transactions that require secrecy. But why should anything about the character of revenues and expenditures be shrouded in secrecy? Why should the decisions made during board meetings be shrouded in secrecy? What can possibly be the rationale for confidentiality in a nonprofit’s proceedings?

The remedy for corruption is transparency. Ahmed (2013, p. 272) writes:

“NPOs maintain their professional accountability, which, as mentioned before, means being responsive to different stakeholders. One of the major processes is public reporting that involves delivering on regular basis authentic information about their operations, effectiveness, challenges, financial sustainability, and other relevant information that is useful to stakeholders. Most of this information could be posted on their Web sites. In this era of communication and technology revolutions, blogs have become an important two-way channel of communication between NPOs and different stakeholders. Public reporting and blogs go a long way to promote NPOs’ transparency, too. Responsiveness also includes NPOs remaining truthful to their mission and their obligation to fulfill donors’ expectations. From the clients’ perspective, responsiveness not only means to serve their needs but also to treat them in a professional way. . . .”

In our conference paper, “Transparency in Nonprofit Organizations: Public Access to Minutes of Board Meetings,” Amanda M. Wolcott‑‑an NGCSU psychology alumna and a 2017 graduate of the University of Central Florida’s Ph.D. Program in organizational psychology‑‑and I assert that charities should publicize their minutes of their board meetings. Examine the Web sites of some charities and notice how many of them have links to such minutes. It rarely happens. I contacted leaders of 17 501(c)(3) organizations here in Dahlonega. In every case, the leaders told me that, if asked, they would disclose their minutes to anyone who requested access to them. Why should anyone donate to a charity that opts to conceal its decision-making process? Why don’t the Better Business Bureau and Charity Navigator include charities’ willingness to publicize minutes of board meetings when they rate the charities? Why doesn’t the IRS require charities to make their minutes public? Perhaps, if a charity asks you to donate, you should request a copy of the minutes of the most recent board meeting. If the charity withholds the minutes from you, perhaps you should withhold your money from the charity. In my opinion, if a board is doing its job responsibly, it should be proud to display its minutes to the public.

In our paper, Amanda asserts that the founder of a nonprofit organization is obligated to create a culture of transparency.

“. . . [T]he founder must actively embody the values he espouses by being transparent himself.

“. . . [F]ounders must truly comprehend the importance of transparency and be mindful in the actions that they take in order to ensure that their organization does not fall prey to a shroud of secrecy once a board is legally in control.”

Ethics and transparency go hand in hand. Americans ought to insist on both of them from nonprofit organizations and give a wide berth to those that prefer secrecy.

VOLUNTARISM

As my students have read my Red Cross case study and we have discussed it over many years, they have been curious about my agitation over the termination of my volunteer status and my motivation for writing a lengthy exposé about the 1995 incident. This has been my explanation: Beginning in 1986, when I went to work for the Fairfax County Chapter, I also became a volunteer. I have a nice little memory: I went downstairs to the office of Safety and Youth Services one day, not long after I started working at the chapter. In this office, the employees had some Red Cross-decorated apparel for sale. I purchased a red windbreaker and a white golf shirt and put them on. Then, I returned to the Office of Volunteer Personnel, directed by Kay Schroeder. I said triumphantly to my boss, “Look, Kay! I’m ready to go out on a disaster operation!” Kay chuckled and responded, “You’ll have to do more than that to be ready to help at a disaster site.” What Kay was referring to was a series of courses that train Red Cross volunteers about how to help disaster victims in the approved Red Cross way. Therefore, when our lead disaster volunteer Al Smuzynski offered a class called “Local Disaster Action in Fairfax County,” I attended it. Later, I attended a three‑hour ARC course called “Introduction to Disaster Services.” Then, when our Disaster Services office offered “Emergency Assistance to Families I and II” one weekend at Fort Belvoir, I attended that, too. Once I had relocated to Georgia, I took more courses. I spent a few days at Converse College in Spartanburg, S. C., living in the college’s dormitory while I took such hard-to-find courses as “Shelter Management” and “Disaster Instructor Specialty Training.” The Red Cross also sent me, at its expense, to Jensen Beach, Fla., for five days so that I could be trained to teach training courses for new disaster-relief instructors. This is a very partial list. In summary, I had spent an enormous amount of time (not to mention money) taking these courses and then practicing what I had been taught to do. Once I was discharged from Red Cross volunteer service, what was I supposed to do with this training and knowledge? To what other job or volunteer position could I transfer this background? Thus, I felt aggrieved because my investment of time had gone to waste, but no government agency or court would recognize for a second that I had a claim for damages because, as far as the government was concerned, I had suffered no tangible loss.

Now and then, one of my students will ask my advice about planning for a career in the nonprofit sector. Because of my experience, I offer this perspective: Trade value for value with any nonprofit organization. Exchange an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay. But think twice before giving the organization 1000 hours of work for 400 hours of pay or, even worse, 10,000 hours of work for no pay, because one has no particular reason to anticipate that the organization will feel compelled to repay the investment. Anticipate the possibility that you will get kicked out like I was. In fact, I know of long-time nonprofit operatives who appear to be exuberant about driving people out of their organizations. Jean Cuthbertson, a member of the Northeast Georgia ARC chapter’s board who volunteered for the ARC for over half a century, was one of them. When Richard and Lois Payton, whom I mention in my Red Cross case study, were driven out of their disaster-coordinator jobs and terminated as volunteers, I asked Cuthbertson--then the chairman of the board's Disaster Services Committee--what she thought about this heartless action by executive director Pamela Watts, chapter chairman Lona Pope, and other board members. Cuthbertson thought that it was just marvelous. In the Girl Scouts in which she had also been a long-time policymaking volunteer, she told me approvingly, when an employee left her job, she was prohibited from being involved in the organization in any capacity for something like three years! I was appalled by the thought that such an organization perceives a need to exile castaways because, heaven forbid, they might disenchant newcomers by divulging what is going on in the organization. There is something really, really insidious about the insiders’ desperation to keep people separated so that interaction is minimized and the diffusion of information is inhibited. As I have said before, if nonprofit leaders are doing things of which they have reason to be proud, they should want information about it to be publicized, not to be suppressed. Be prudent about how much you give away to these people!

Lastly, I address the matter of whether the employees and volunteers of nonprofit organizations are psychologically distinctive compared to the rest of the population. Conventional wisdom is that the nonprofit sector is staffed by angels who care about others more than they care about themselves. If I hadn’t encountered so much mean-spiritedness during my nonprofit adventures, I might think so, too. Presumably, the nonprofit sector will attract workers who are interested in social service more than they are interested in corporate profit and dividends. But I believe that people pursue employment in the nonprofit sector for situational reasons. Pay in the nonprofit sector tends to be less than pay in the for-profit sector for two main reasons: First, nonprofit organizations are relatively underfunded so, to make sure that the organization will make its payroll, it has to be conservative in setting pay levels. Second, the level of pay for human-service jobs is routinely lower than it is for jobs in profit-making settings because human-service jobs are more fulfilling for most people and their employers do not need to bribe them to do such jobs with generous pay and benefits. Accordingly, nonprofits are staffed mainly by workers who can afford to work for low pay. This will not work very well for, say, men who are supporting a family or women who are single mothers or even living alone. Thus, my observation is that the nonprofit workforce is dominated by women who are supplementing their husbands’ incomes. At present, I can’t back that analysis up with research so, if your observation is contrary to mine, feel free to share it with us. If my observation is correct, then the low pay causes relatively high turnover, and the people who can afford to take the low-pay jobs will be able to find such jobs readily in nonprofit organizations.

Fifty or 100 years ago, volunteerism was dominated by housewives of mostly well-to-do professional men. These housewives had time to kill and, in many cases, were motivated by a social and moral obligation to help the poor on the principle of noblesse oblige (the nobility has an obligation to be kind and generous toward the commoners). The symbolic figure of this traditional volunteerism is sometimes called “Lady Bountiful.” Today, idle housewives are hard to come by. While some volunteers may be motivated by altruism, many others are motivated by self-interest. When I worked in the Office of Volunteer Personnel at the Fairfax County ARC chapter, I interviewed one high-school student after another who professed intense interest in being a Red Cross volunteer, and I “placed” them in one position or another (such as serving cookies at bloodmobiles). We never saw most of them ever again, but I am pretty sure that every one claimed on an application for admission to college that he had been a Red Cross volunteer. College students may volunteer because they need service or internship credit or because their fraternities or sororities want to burnish their reputations. Young adults may volunteer to obtain new skills and to develop entries for their résumés. Business professionals may volunteer to serve on boards or committees because their employers require them to be involved in the community for networking reasons and to satisfy the employer’s need to appear socially responsible.

In summary, it is an error to assume that nonprofit workers share common altruistic motivations. The nonprofit workforce is heterogeneous, and the workers’ motivations vary and are generally unpredictable.

THE MISGUIDED CHARACTER OF STATE CORPORATION LAWS

Common provisions of state laws impose on board members the duties of care, loyalty, and obedience. As Tschirhart and Bielefeld (2012, pp. 204‑205) explain the duty of loyalty, they state:

“Once a board has made a decision, each board member is expected to stand behind it or resign from the board. However, board members may still wish to record their dissent from a decision on the record. This may protect them from personal liability if this decision is later found to be in violation of board duties or connected to illegal activities. Board members are also expected to respect confidentiality in relation to the nonprofit’s legitimate activities.”

Think this through with me. There is no room for dissent in board deliberations. If a board member believes that the majority is doing something improper, she can acquiesce to the misconduct or quit. Even if she quits, she is legally constrained from telling anyone, even other members and field volunteers of the organization, about her objections. This makes it impossible for the organization’s members and field volunteers to intervene in organizational misconduct that is being kept a secret from them. How does this situation promote accountability? What kind of transparency can this be? How can this possibly serve the public interest?

As I understand it, a dissident board member may report misconduct to law-enforcement officials, the state’s attorney general’s office, and/or the U. S. Internal Revenue Service. The IRS even has a form, Form 13909, “Tax-Exempt Organization Complaint (Referral) Form.” I don’t think that a board may sue a dissident for blowing the whistle by truthfully notifying these government authorities about misconduct. However, if the dissident discloses the misconduct by informing organization members or the local newspaper, the board can sue her for violating her duty of loyalty and the board will have her on the ropes. Incidentally, a dissident's whistle-blowing report to government authorities rarely results in repercussions to the nonprofit organization. Law-enforcement officials are much too busy arresting folks for possession of half an ounce of marijuana. The IRS doesn't have nearly enough personnel to review complaints. As an IRS agent once told me as I was submitting a Form 13909, "We get thousands of them."

Comedian Jerry Lewis served as the chairman of the board of the Muscular Dystrophy Association for decades and hosted annual fund-raising telethons from 1952 to 2010. He raised $2.6 billion in the process. In 2011, the association announced that Lewis had been ousted from his volunteer-leadership position and banished from the Labor Day telethon. Why? The association has never divulged the reason, and Lewis was uncharacteristically silent. Many observers have wondered whether Lewis had developed doubt about the association’s progress in discovering a cure for muscular dystrophy after $2.6 billion had been raised for that purpose. An August 20, 2017, CBS News obituary written by Justin Carissimo reported:

“The money led to longer life spans for those patients, but it didn't buy a cure. At times, Lewis could only watch as the disease claimed the lives of children.

“‘The days and hours I spent in hospital hallways waiting for the answer of this child‑‑was he going to live or die? And I took it very personal,’ Lewis told CBS News in 2016. ‘How could he die? Look at the work I've done. And what did we do with all that money? Why don't we use it to help him?’” [emphasis added].

But Lewis couldn’t say any more than that because of the confidentiality rule. Let’s consider this question: Why should the public know why Lewis and the MDA’s board had this parting of the ways? If we don’t know, then how are Americans supposed to make an informed decision about whether to donate to the MDA? Remember that the capitalist model assumes that the parties to a transaction have perfect information. In the MDA case, there cannot be perfect information, because the laws muzzled Jerry Lewis. The authors of our own textbooks state that the nonprofit sector is designed to serve the interests of the entire public. I contend that the system is not designed to do any such thing but is, instead, designed to satisfy an elite community that controls nonprofit organizations, not to mention the other significant institutions of American society.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ahmed, Shamima. (2013). Effective Non‑profit Management: Context, Concepts, and Competencies. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC Press.

Bakal, Carl. (1979). Charity U.S.A.: An Investigation Into the Hidden World of the Multi-billion Dollar Charity Industry. New York: Times Books.

Bennett, James T., and DiLorenzo, Thomas J.

(1994).

Unhealthy Charities:

Hazardous to Your Health and Wealth.

New York:

Basic Books.

Grobman, Gary M. (2015). An Introduction to the Nonprofit Sector: A Practical Approach for the 21st Century. 4th ed. Harrisburg, Penn.: White Hat Communications.

Newhouse, Joseph P. (1978). The Economics of Medical Care: A Policy Perspective. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Tschirhart, Mary, and Bielefeld, Wolfgang. (2012). Managing Nonprofit Organizations. San Francisco: Jossey‑Bass.

.

Personal disclaimer: This page is not a publication of the University of North Georgia and UNG has not edited or examined the content of the page. The authors of the page are solely responsible for the content.

Last updated on April 9, 2019, by Barry D. Friedman.

Back to Barry D. Friedman's home page . . .