|

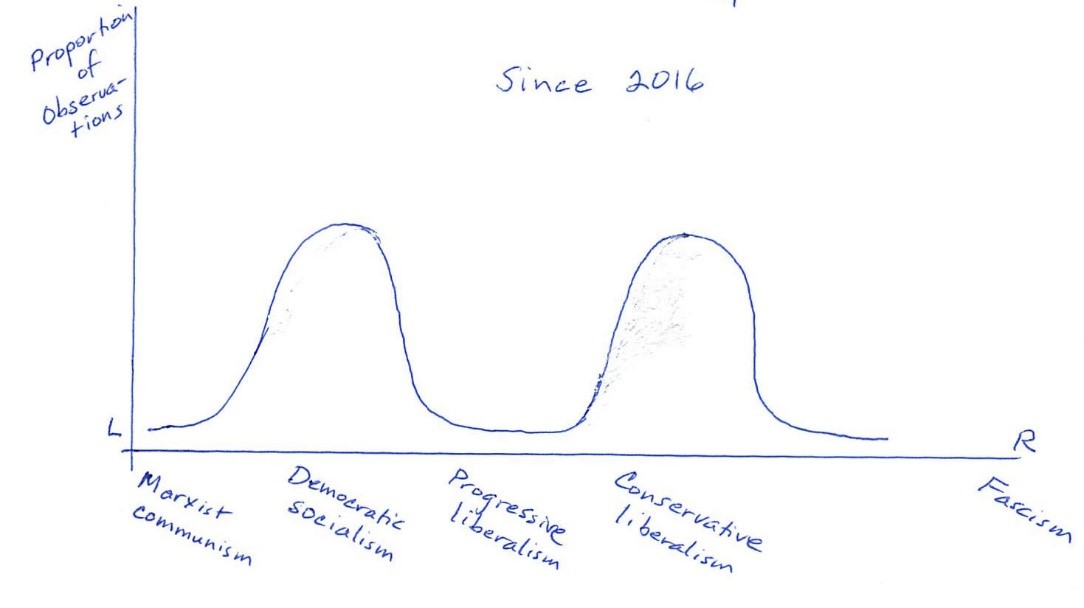

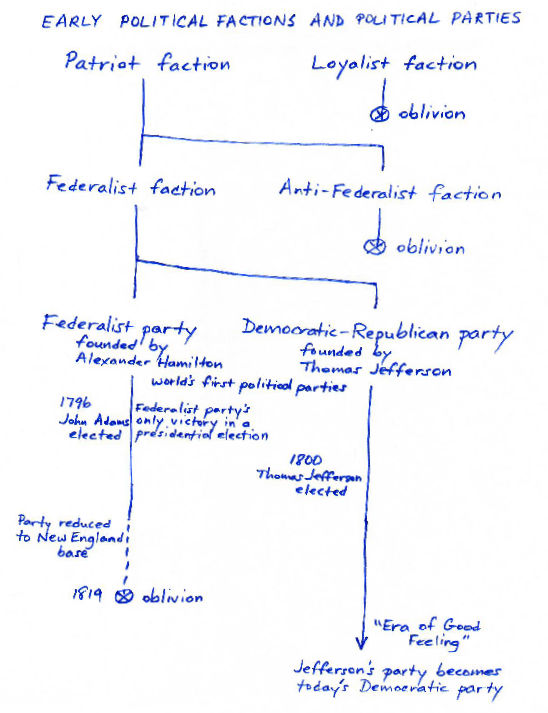

EVENTS THAT HAVE TAKEN AWAY THE POWER OF POLITICAL-PARTY

OFFICIALS

For many decades in American history, the political-party

organizations and their leaders had significant influence

over political campaigns, elections, and public policy.

However, events over the past 140 years have

drastically eroded the power of the political-party

organizations and their leaders.

Here is a discussion of these milestone events.

1.

Civil Service Act of 1883

After about half a century of experience with the “spoils

system” that President Andrew Jackson established when he

was elected in 1828, Americans decided that the spoils

system encouraged corruption in the national government.

The assassination of President James Garfield by a

so-called “disgruntled job seeker” was the final impetus for

Congress to enact the Civil Service of Act of 1883, whose

purpose was to begin the phasing-out of the spoils system

and the installation of the civil-service or “merit” system.

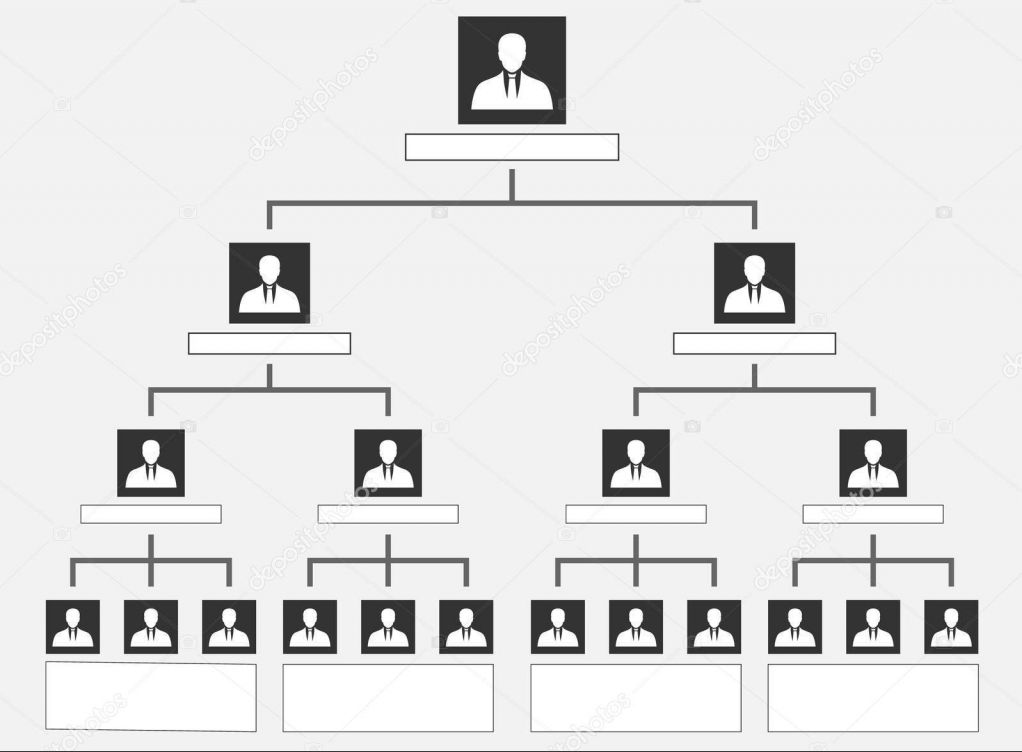

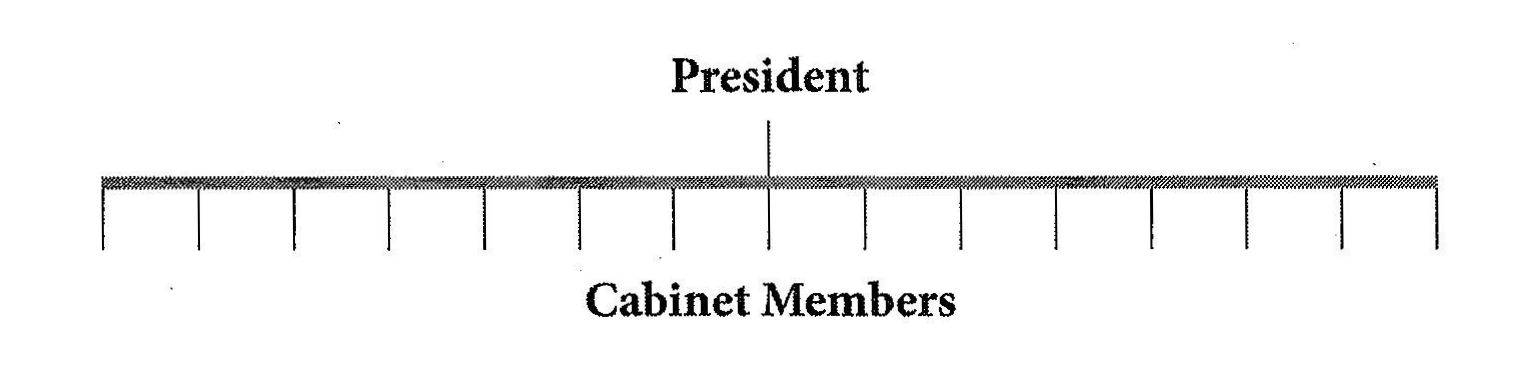

Jobs in the national government’s executive branch

below the policymaking level (i.e., below such positions as

Cabinet members, agency directors, and their immediate

subordinates) are covered by the civil service.

This includes a variety of professional jobs such as

agents, analysts, inspectors, accountants/bookkeepers,

scientists, engineers, etc.

It is a violation of the Civil Service Act of 1883

for appointments to those jobs to be determined based on

partisan affiliation.

The only acceptable criterion for appointment to the

civil service is merit.

This law eliminated influence by the party organizations and leaders in the

selection of executive-branch employees below the

policymaking level.

(At the policymaking level‑‑the highest levels in the

executive branch‑‑the appointments are “partisan

appointments” and the appointees are selected by the

president and his assistants.

The president is entirely entitled to take political

loyalty into consideration when he makes these partisan

appointments.)

2.

The “seniority system” was installed as a reform to break up

the speaker’s oligarchy (Joe Cannon vs. Champ Clark)

Up until 1910, the speaker of the U. S. House of

Representatives had enormous power over the

legislative/policymaking process.

He single-handedly decided who would be the chairmen

of the standing committees.

He also determined who would be the members of the

House Rules Committee, which determines which bills will

come to the House floor for debate and a vote.

The speaker worked closely with the chairman of his

party’s national committee and, together, they could decide

which policies would be established by law and which ones

would not. In

1910, there was an uprising against the last of the

all-powerful speakers‑‑Republican Joe Cannon‑‑led by Champ

Clark. Cannon

was ousted. The

members of the House took away the speaker’s unilateral

power to appoint the chairmen of the standing committees.

Thereinafter, on each standing committee, the

committee member who belonged to the majority party and had

the most seniority on the committee automatically became the

chairman. This

took enormous power away from the position of speaker and

from the position of the party’s national chairman, in so

far as they could not dictate policy anymore.

3.

The Hatch Act was enacted in 1939, prohibiting

national-government civil-service employees from openly

participating in politics

Even after the civil-service system had been installed to

reduce the power of the party organization and leadership

(so that they could not control appointments to

executive-branch positions as they did during the days of

the spoils system), suspicion persisted that, somehow, the

party leaders were still involved in placing loyal party members into government jobs

and that such loyal members were tithing their pay to the

political parties.

Therefore, to extinguish the link between the

political-party organizations and the civil service,

Congress enacted the Hatch Act of 1939.

This law prohibited civil servants from openly

participating in politics.

Thereinafter, they could not be a member of any

political organization or committee, they could not donate

to campaigns, they could not put yard signs in front of

their homes indicating their support for a candidate, etc.

4.

Primary elections for nominations took party leaders out of

the process (no more “smoke-filled rooms”)

In the 1910s, Robert La Follette of Wisconsin led the

Progressive Movement.

The centerpiece of the Progressive Movement’s beliefs

was a familiar one in American political history:

The movement’s

members were convinced that all of the corruption in

American politics originated in the political-party

organizations.

They demanded that the power to decide who the parties’

nominees for elected offices would be should be taken away

from the party leaders (who were denounced as “kingmakers”

who would make such decisions in “smoke-filled rooms”) and

transferred to the voters through the use of party primary

elections.

Journalists joined the Progressives’ demands that primary

elections become prevalent for selecting party nominees.

State by state, legislatures changed election laws to

require primary elections.

A principal influence of party leaders‑‑selection of

party nominees for elections‑‑was gradually eliminated

across the United States.

5.

U. S. Supreme Court:

Smith v. Allwright (1944) – “white primaries”

are illegal; parties are “inclusive”

In many of the racist, mostly southern, states, one of the

tricks used by the white, racist, elite class to

disfranchise black citizens was to declare the Democratic

state organizations to be private associations and to say

that, as private organizations, they possessed the right to

deny membership to black citizens.

Thus, the Democratic primaries in these states were

“white primaries.”

The nature of the abuse of this arrangement was based

on the Democrats’ monopoly of politics in the “Solid South”:

These states had banished the Republican party after

the Civil War to punish the party for prosecuting the war

against the southern states.

If Democratic voters could not vote in the Democratic

primaries, then, by the time that they

could vote in the general election, there was only one candidate

for each position:

the winner of the Democratic primary.

Thus, there was no way for black voters to have any

influence over who would get elected.

The U. S. Supreme Court accepted the case of

Smith v. Allwright,

321 U.S. 649 (1944).

In this case, the Supreme Court rejected the

Democratic state organizations’ claim to be private

associations; instead, the court said that these

organizations are unmistakably

public because of their influence in the process of elections.

The side-effect of the court’s opinion is that, since

then, the law has recognized that American political parties

are inclusive.

That means that anyone who wants to join either party

has the unqualified right to do so.

This characteristic of the political parties

decreases the party organizations’ and leaders’ power in

this regard: If

anyone who wants to be a member of either party is free to

do so, then the party leaders have very little ability to

impose discipline

on members.

Notably, the leaders lack the power to use

excommunication as

a form of discipline over disloyal individuals.

6.

Television allowed candidates to take their case directly to

the people

In the 1950s, many Americans purchased a new piece of

furniture for their living rooms:

television sets.

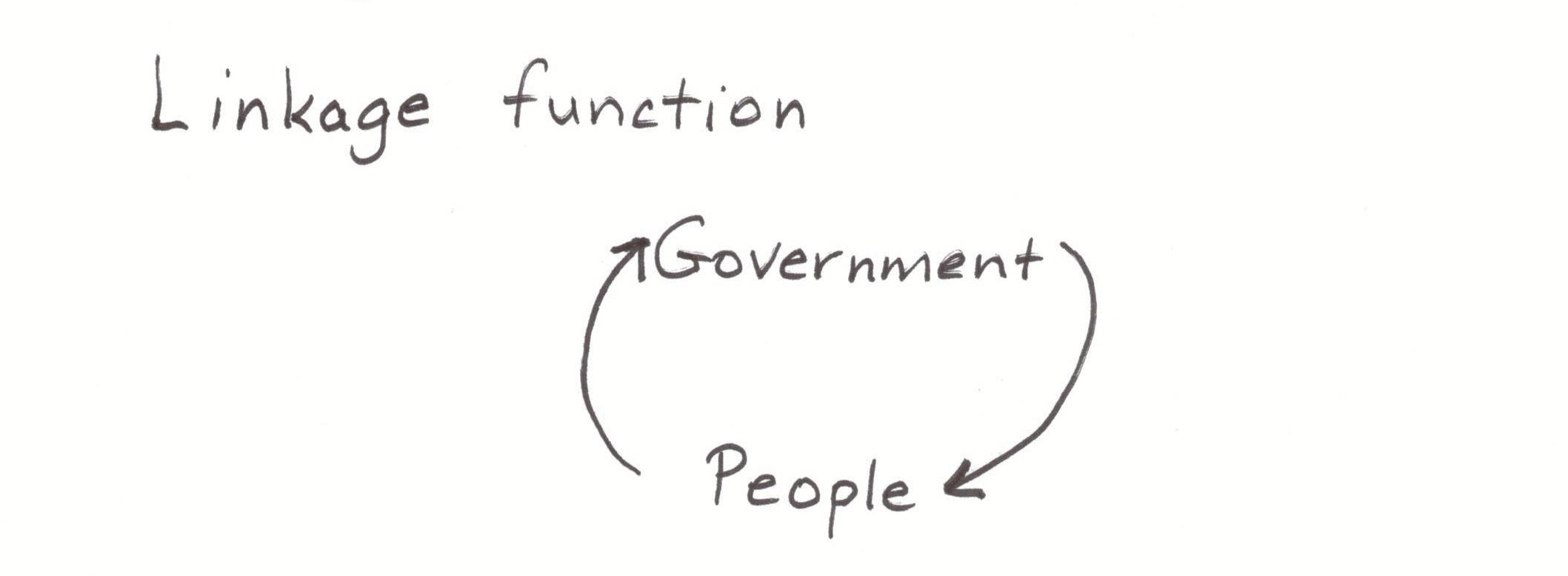

The development of television stations and networks

excited the political parties’ leaders:

They anticipated that they could use the new medium

to carry out their

linkage function by sending messages over the airwaves

to the public to support the parties’ platforms and

candidates.

However, candidates had their own idea:

They could run their campaigns

independent of the

political-party organizations by appearing and advertising

on television!

Over time, it has become clear that the candidates’ vision

prevailed: The

vast majority of campaign advertisements are now made by and

paid for by candidates’

campaigns. “I’m

John Doe and I approve this message.”

Rare are campaign ads offered by, say, a Republican

State Central Committee advocating that voters should vote

for the Republican ticket in an upcoming statewide election.

7.

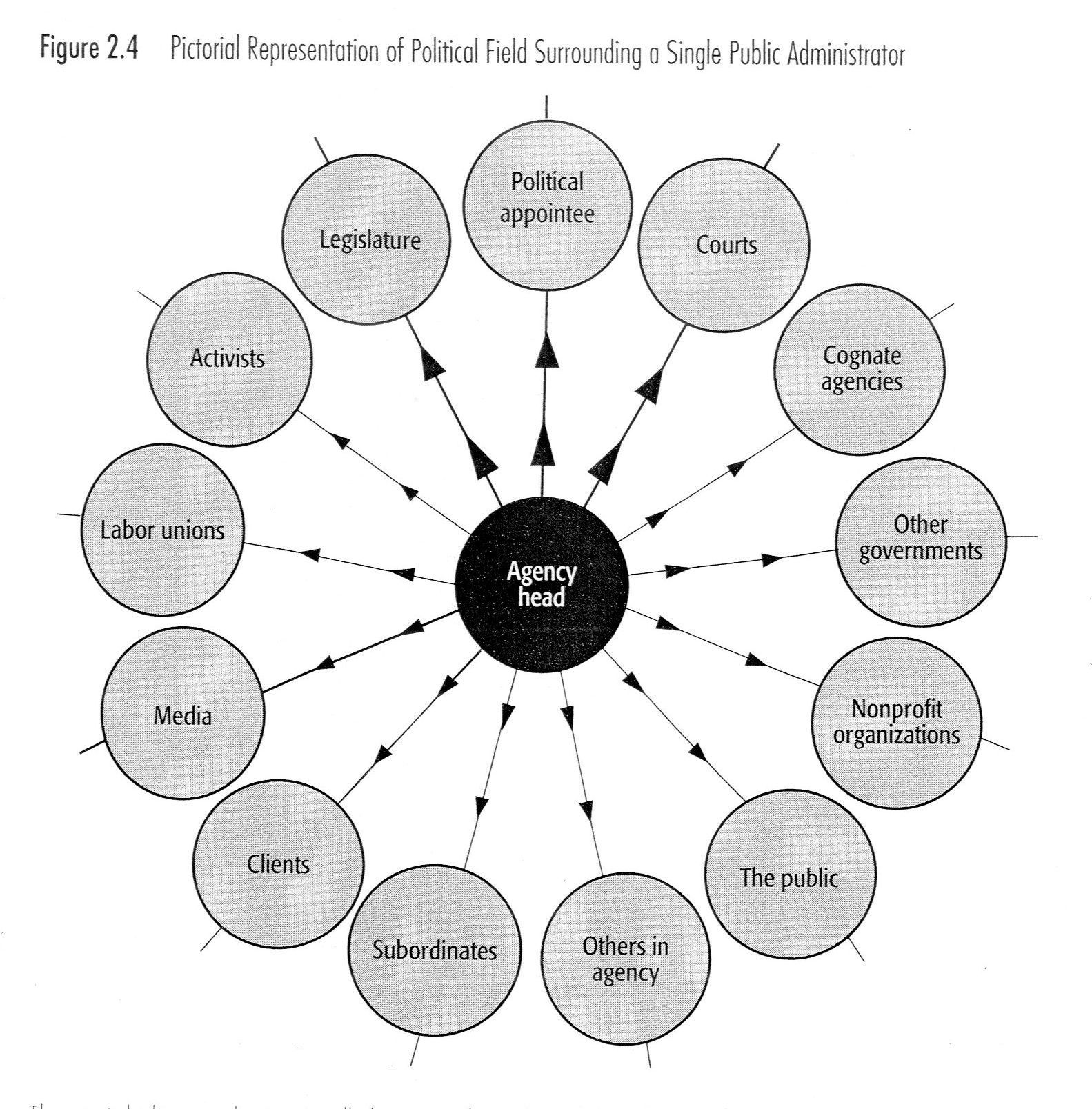

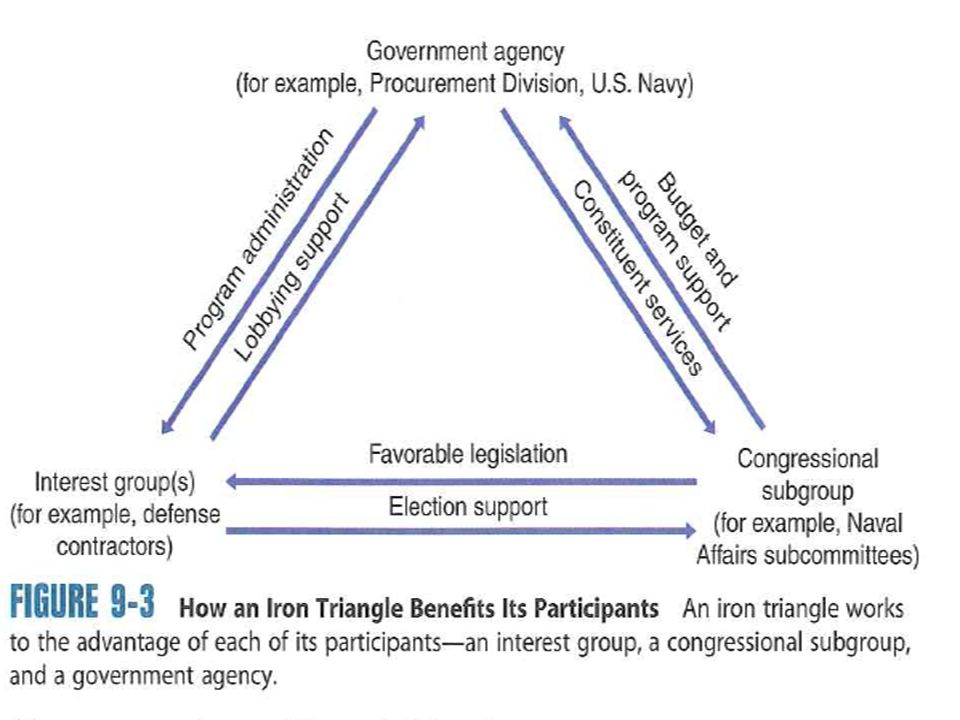

Members of Congress took over the “liaison” (ombudsman)

function

The ability of political-party leaders (e.g., local ward

chairmen and precinct captains) to deliver services to

individual party members has generally declined as

legislators have developed the function of

constituent service

(often known informally as “case work”).

Today, when a citizen is not getting a service from

the executive branch to which she believes she is entitled,

she does not contact a political-party leader.

Instead, she contacts the office of her U. S.

senator, U. S. representative, or state legislator,

depending on which level of government has the service to

which she feels entitled.

Legislators essentially stole this way of

ingratiating themselves with the public from the

political-party organizations.

8.

McGovern-Fraser Commission

In 1968, Democrats held a disastrous Democratic National

Convention in Chicago.

The delegates assembled there to nominate a candidate

for president.

Outside Chicago’s International Amphitheater, a variety of

anti-Vietnam War activists and civil-rights demonstrators

rioted in the streets.

The turmoil seeped into the arena, and the delegates

proceeded to demonstrate heated animosity toward each other.

The Democratic ticket led by Vice President Hubert H.

Humphrey went down to a painful defeat that November.

In the aftermath of this misfortune, the Democratic

National Committee appointed a Commission on Party Structure

and Delegate Selection.

The commission became popularly known as the

McGovern‑Fraser Commission, after the two members of

Congress who served as the chairmen at various times.

The commission focused on a deficiency of both

parties’ national conventions.

Those of us who would watch the conventions on

television would notice that the delegates were almost

uniformly older, affluent, white men.

These older,

affluent, white men, by the way, were almost all experienced

party leaders and their loyal supporters.

Thus, the commission developed rules that would

require state delegations at subsequent conventions to

properly represent women, black voters, Hispanics, laborers,

and young people.

The Democratic National Committee implemented the

commission’s recommendations.

When it was time for the 1972 Democratic convention

to convene, this time the delegates actually did include a

proportionate number of women, black voters, Hispanics,

laborers, and young people‑‑and, if the truth be told, they

were to a large extent

amateurs. A

lot of the older, affluent, white, male

party regulars‑‑many

of them members of Congress, state legislators, and other

experienced party activists‑‑were watching the convention on

television in their homes.

The amateurs bypassed former Vice President Humphrey,

who was making another attempt to become president, and

instead nominated U. S. Sen. George McGovern (D‑S. D.).

McGovern ran an anti-Vietnam War campaign during

which he presented the possibility that, as president, he

might pay a call on North Vietnamese Communist dictator Ho

Chi Minh and, on McGovern’s hands and knees, beg Ho for

peace. The

imagery troubled countless voters.

Republican incumbent Richard Nixon cleaned up the

floor with McGovern.

Causing the “party regulars” to stay at home and

allowing amateurs to make the final decision about the

Democratic nominee was just another insult for party leaders

and an indication of what happens when their power is taken

away.

Incidentally, to dampen the effect on the diversity rules

that excluded party regulars, the Democrats later added a

class of delegates known as “superdelegates”‑‑elected

government officials who would become delegates

automatically (i.e., without running in state presidential

primaries) and balance the diverse amateurs with their

experience.

Years, later, the presence of “superdelegates” would

complicate and inflame the bitter competition between

candidates Hillary Rodham Clinton and Bernie Sanders during

the 2016 contest for the Democratic nomination for

president.

Sanders’ supporters have been bitter about the effect of the

superdelegates, who overwhelmingly supported Clinton, ever

since.

9.

Nixon’s Committee to Reelect the President

President Nixon’s 1972 reelection campaign remains famous as

a milestone event because his campaign was

not run by the

Republican National Committee.

Instead, his campaign was run by his own candidate

committee, the “Committee to Reelect the President.”

The RNC’s chairman, Bob Dole, was irritated about

being bypassed in this manner, and referred to the committee

contemptuously as “CREEP.”

The committee ended up securing

another prominent

place in American history:

Operatives of the committee burglarized the

Democratic National Committee’s headquarters at the

Watergate hotel and office complex in Washington, D. C., as

they hoped to steal documents that would reveal the

Democrats’ campaign strategy.

The operatives were caught in the act and arrested.

A lengthy investigation followed.

Hoping to cover the operatives’ tracks, President

Nixon instructed his chief of staff and assistant for

domestic policy to direct the Federal Bureau of

Investigation to terminate its investigation to protect (nonexistent)

national-security secrets.

On account of obstructing justice by trying to

mislead the FBI, the president was forced to resign in

August 1974.

Arguably, he almost

ended up in a federal penitentiary, were he not pardoned by

his successor, Gerald Ford.

In fairness, it should be pointed out that Nixon’s decision

to entrust his reelection campaign to his own campaign

committee was not an irrational thing to do.

In modern times, thanks to such influences as La

Follette’s Progressive movement, political-party

organizations and leaders do

not decide who the

parties’ nominees will be.

Instead, every person who aspires to be elected has a

need, on her own, to secure the party’s nomination and‑‑to do so‑‑she

has to run against other aspirants in her party’s primary

election.

Obviously, the party organization is in no position to run

each such candidate’s primary campaign.

Each candidate must establish her own campaign

committee to help her win the primary.

Once one of the candidates has won the primary, is

she inclined to

dissolve her committee and turn her campaign over to the

party organization?

Of course not!

Her campaign committee has proved to be a winning

team.

Inevitably, she will rely on this committee to help her win

the general election.

10.

Transition committees

One might think that, when a candidate for president of the

United States has won the general election and he now has

about 3000 partisan appointments to make, he will call on

the chairman of his party’s national committee to help him

decide whom to appoint.

One who thinks that would be wrong.

In recent decades, the president-elect has

reorganized his campaign committee into a transition

committee, which will help the incoming president fill the

3000 positions.

The transition committee collects recommendations, résumés,

and other resources, and advises the new president how to

fill the partisan appointments.

The political-party organization is uninvolved in

this process, too.

11.

Open primaries

About half of the states have election laws that call for

“open primaries.”

Open primaries are the final insult to our

political-party organizations as policy-oriented

institutions.

Open-primary laws allow any voter‑‑regardless of any notion

of party affiliation‑‑to vote in either party’s primary on

primary-election day.

This allows, for example, unaffiliated voters

(“independents”) to vote in the Republican primary.

It even allows

Republicans to vote in the

Democratic

primary! The

original notion of political parties is that each political

party would present for the election a nominee who

represents the party’s policy-oriented mission.

Open primaries turn this notion into a joke.

They indicate just how much contempt our American

political system developed for the significance and

coherence of political parties.

The developments described above have certainly dispirited

political-party leaders.

Then-RNC chairman Bob Dole was trying at one point to

make an appointment with President Nixon.

He got as far as being able to discuss the matter in

a telephone call with Nixon’s chief of staff, H. R. “Bob”

Haldeman. Dole

later reported this only-somewhat-fictionalized dialogue:

DOLE: I'm the

national chairman and I need to see the president.

HALDEMAN: You

need to see the president?

Tune in Channel 9 tomorrow night at 10 o'clock.

An NGCSU political-science alumnus, Michael Shane McGonigal,

told me about how he was an intern in Washington, D. C., and

at a gala event he met Ken Mehlman, then Republican national

chairman. “Wow!”

Shane said.

“You’re the national chairman!

You are a powerful man!”

“Not really,” Mehlman replied.

“I’m just a glorified fund-raiser.”

|